Episode 26: The Messiah Goes to Japan

Come walk this dark path of mistrust and persecution to learn more about the history of Christianity In Japan and Christian traditions unique to their culture.

Listen To Learn More about:

The Japanese tomb for Jesus Christ

The largest rebelion in Japanese history, Shimabara Rebellion, and why it happened

Early Christian Missionaries in Japan

Japanese leaders like Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu

Ieyasu Tokugawa

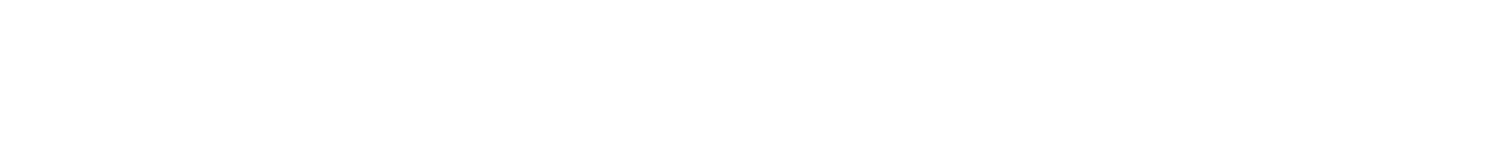

Map of Japan with highlight on Aomori Prefecture

Hakkaku Endo-Mount Osore

Buddha at Kamakura in Japan

Boeing B Superfortress

Aomori at Night

Aoni Onsen in the Mountains of Kuroshi

Atomic bombing of Japan

Jaroslav Čermák

Uroš Predić - Sveti Nikola

Franciscus Xavier one of the first Christian Missionaries in Japan

Toyotomi Hideyori

Sources

References/ Additional Reading

Smithsonian Magazine: Jesus In Japan

Japan Times: National Aomori Plugs its Power Spots

Yamada Futaro. Makai Tenshō. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1967.

Oda M. “Distribution of Christianity in Japan.” Pennsylvania Geographer 37.1 (1999): 17-32.

J. Thomas Rimer, “Four Plays of Tanaka Chikao.” Monumenta Nipponica XXXI.3 (1976): 280

Tanaka Chikao, Maria no Kubi. In Gendai nihon gikyoku taikei 4. Tokyo: San’ichi shobō, 1971.

Susan Napier, The Fantastic in Modern Japanese Literature (New York: Routledge, 1996

Miura Ayako, Hosokawa Garasha Fujin (Tokyo : Shūfu no Tomo-Sha, 1975.

Endo Shusaku. A Life of Jesus. Trans. Richard A. Schuchert. New York: Paulist Press, 1978.

Harrington, Ann M. Japan’s Hidden Christians. Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1993.

Kaiser, Stepan. “Translations of Christian Terminology into Japanese 16th-19th Centuries: Problems and Solutions.” Breen and Williams. 10-25.

Mullins, Mark R. Christianity Made in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1998.

Turnbull, Stephen. “Acculturation among the Kakure Kirishitan: Some Conclusions from the Tenchi Hejimari no koto.” Breen and Williams. 63-74.

. “Written and Unwritten Texts of the Kakure Kirishitan” Breen and Williams. 122-137.

Endo Shusaku. The Golden Country. Trans. Francis Mathy. London: Peter Owen, 1989.

Takado Kaname. “Japanese Christian Writers.” Trans. Noah S. Brannen. Christianity in Japan, 1971 – 1990. Eds. Kumazawa Yoshinobu and David L. Swain. Tokyo: Kyo Bun Kwan, 1991. 259-270.

Full Script

This is the My Dark Path podcast.

The holidays are upon us, and everyone here at the show is proud and excited. We’re coming to the finish of our first season, and I don’t mind saying that it feels like a bit of a holiday miracle. We’ve produced 26 episodes in our first year of existence, and while we often felt like we were building the plane while we were flying it, we never missed a release date, and I’m incredibly proud of the team we’ve assembled, the stories we’ve told, and the standard we’ve set for a podcast that aims to intrigue and excite, while paying the proper respect to history and science.

We’re going to take a couple of weeks off after this episode, but Season 2 is already in the works – we’ll be launching on January 11th with an incredible tale of naval exploration and disaster, the true story of the quest for the Northwest Passage in the Arctic. And we have plans in place to offer some exclusive, premium content for people who want to become a part of bringing this show to life – I can’t wait to share more with you about that. But the team has earned the time to celebrate these days however it suits them.

The holidays offer unique pleasures to the history nerd, since behind every celebration is a fascinating blend of facts and folklore, of tradition and evolution. Anytime you think to yourself that this is just the way it’s always been done, the truth turns out to be far more intriguing. Take Santa Claus, the beloved gift-giving mascot of Christmas with his team of reindeer and his workshop on the North Pole. Did you know that his bones are in Italy?

That’s one way to look at it. Many of the myths around the figure we call St. Nick begin with a 4th-century Greek Bishop, born in modern-day Turkey, known as St. Nicholas of Myra, or Nicholas the Wonderworker. Legends tell of his exploits as a secret gift-giver to the poor – in one of the most popular stories, a local Christian lost all his wealth to misfortune, and with no dowry for his three daughters; he feared that they would be forced into prostitution after his death. St. Nicholas, the story goes, threw a bag of gold through his window at night. After his death, what are believed to be his remains were moved multiple times as territory changed hands during the Crusades; to the best of our knowledge now, they were actually split up in the 11th century, and some of his bones are in Venice, and the rest are in the Basilica di San Nicola in the southern Italian city of Bari.

It’s a long way to get from a long-dead bishop with a chopped-up skeleton to the figure we know as Santa today, and it passes through the English tradition of Father Christmas, the Old Norse God Odin, the legendary American poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas”, and some drawings by the 19th-century cartoonist Thomas Nast. For me, knowing the incredible history behind the modern image of the jolly old elf at the North Pole only makes him more fascinating.

But Christmas isn’t just Santa’s holiday; after all, it’s there in the name – for Christians, it’s the day to celebrate the birth of Jesus. And even people who don’t share Christian beliefs probably know a few of the highlights – being born in a manger to a virgin mother, working as a carpenter, gathering his Apostles to spread the word of God, and dying by crucifixion at the hands of the Roman Empire.

We’re not going to unpack that story here – rather, I want to take you far away from the Holy Land, to tell you a story about Jesus you’ve probably never heard of. One that mixes history and legend and mystery in a way that we couldn’t resist learning more about. And it all takes place…in Japan.

***

Aomori Prefecture is the northernmost part of Honshu, the main island of Japan. While we think of Japan as a densely-populated country, most of Aomori is nothing like the hustle and bustle of Tokyo. It’s miles of forest-covered mountains, barely touched by the modern world. The people who live there are primarily fishers and farmers; although some have started to make their living in the tourist trade, because for a number of reasons, curious people are drawn to visit here.

There have been numerous reports of UFO sightings; and you know how irresistible that is to us at My Dark Path. A Buddhist Temple called Mount Osore sits in the caldera of an active volcano, and local tradition holds that it is one of the gateways to hell. In 1935, a small, stone pyramid was discovered, centuries old and with no clues to its origin; it’s one of many sites in the prefecture which locals claim have healing energies. There’s also a rich collection of local ghost stories.

But the site which causes the most curiosity sits on top of a little hill in the small town of Shingō, far up winding roads through the mountains and east of Lake Tawada. The town has less than 2,500 people, most of the land is dedicated to yam farms and cattle ranches. This little hill sits just on the outskirts, on a site that’s maintained by a local yogurt factory. The entry fee is just 100 yen, less than a dollar; but some 20,000 people a year come to this little hilltop in this faraway town, where there are two centuries-old burial mounds, each surrounded by a white picket fence. And, in a country where Christianity walked a very dark path after missionaries first arrived here, these ancient mounds are each topped with a wooden cross.

Because here in Shingō, in the Aomori Prefecture of Japan, the locals will tell you with absolute faith, is where Jesus of Nazareth, the son of God, is buried, having died there at the age of 106.

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 126: The Messiah Goes to Japan.

PART ONE

We’ll tell you the Japanese version of Jesus’s life story later – it’s important first that we lay some groundwork about the tumultuous history of Christianity in this nation. To this day, less than one percent of the population is Christian – the dominant religion in Japan is a unique blend of Buddhism and the ancient ways of Shinto, the native Japanese belief that there are kami, gods and living spirits, inside all things. We’re going to dig deeper into this captivating belief system next year on our Valentine’s Day episode about the legend of Yaoya Oshichi, the Fire Maiden.

But, to the best of our knowledge, Christianity first reached these islands in the mid-16th century; 1549 to be exact. It was only six years after the first known Europeans visited this island nation – a group of Portuguese merchants who landed on the island of Tanegashima, and traded flintlock firearms and gunpowder to the locals.

Christianity arrived here, as it did in many places during this period, with a group of Jesuit missionaries. A group of them in Malacca in Southeast Asia were visited by a man we know only by the name Anjiro. He invited them to visit his country; said that it would be receptive to Christian beliefs, that the Japanese were ready to convert. And while it took some time to answer his invitation, in July of 1549, the missionary Francis Xavier, and three other Jesuit priests, made the journey. But for three weeks, every port they attempted to dock at refused to let them enter. Finally, on August 15th, they were allowed to land at Kagoshima, on the island of Kyushu. The reality, they soon learned, was much more complicated than what this Anjiro had promised them.

How do you tell a foreign culture a story about a man who had died over fifteen centuries before; and then ask them to change how they view the world, the gods, the afterlife, the origins of life, how they should worship, the morals they live by, all because of this story? And how do you do it when you don’t even understand the language? How do you express concepts like resurrection, like the Holy Trinity, in a culture with completely different frames of reference about life and death? The Jesuits weren’t working with a spiritual blank slate, they were entering into a rich, sophisticated, powerful belief system built on ideas and assumptions wildly different from their own.

But Francis was more than just a devout follower – he was a skilled diplomat. He made a positive impression on the local daimyo, the feudal lord who ruled over the people who lived and worked on his land. He also helped broker relationships between the Japanese and the increasing flow of Portuguese traders. Japan was still far from being unified, and among competing warlords there was a natural interest in European technology, and European firearms. We have no record of whether the Jesuit Francis Xavier saw this as a worthy thing to facilitate in the name of converting people.

He couldn’t speak Japanese, but the Jesuits have always believed in rigorous study and self-improvement, so he worked hard at it. And he got traction when he started to refer to the Christian God as “Dainichi” – a Japanese name for Buddha. And here’s where you start to see the almost impossible barriers of understanding to what the Jesuits wanted to do – because to the Buddhists, Buddha is not an all-powerful god, but a human who achieved transcendence, an enlightened teacher who showed followers the path to Nirvana. In Buddhism, resurrection isn’t a miracle that only a Messiah can perform, every person is part of a long cycle of birth and rebirth that continues until we learn to rise above Earthly desires.

Francis Xavier was successfully building a bridge by adopting terms and concepts that the Japanese understood; but to many Japanese, including the samurai class and even Buddhist monks, this “Christianity” he spoke of simply sounded like another form of Buddhism. This culture had already synthesized Buddhism with Shinto; perhaps that what was happening for some in this case.

The missionaries brought paintings and other Christian artwork. They brought plays and other forms of performing arts that could be translated into Japanese, trying to tell Christian stories to followers of a foreign faith. All told, Francis Xavier spent two years in Japan before returning to India.

When he left, he had established a thriving Jesuit mission in the growing port town of Nagasaki. By 1579, thirty years after Francis’s arrival, an estimated 130,000 Japanese were practicing Catholics. Nagasaki became known as “The Rome of Japan” due to the sheer number of not just Christians, but clergy as well. By 1590, half the Jesuits in Japan were of Japanese birth.

The Jesuits expanded their mission, and actively cultivated influence with the government, both locally and nationally. A powerful warlord named Oda Nobunaga was celebrating a string of military victories, and seemed within reach of unifying the nation. A Jesuit companion of Francis Xavier by the name of Luís Fróis was trusted by Oda, even lived in his home. But the warlord died before realizing his ambition; betrayed and ambushed in the middle of a tea ceremony, he asked a page to set his temple on fire so no one could claim his head as a trophy, and then committed seppuku, suicide by ritual disembowelment.

His successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, brought Japan even closer to unification under a single military ruler; but his attitude towards Christianity took a turn. When he saw that some Christian daimyo were destroying Buddhist temples in territories that they conquered, he became concerned that this new religion might not synthesize harmoniously into Japanese culture; that it showed signs of being intrusive and intolerant; a possible threat. He confronted Christian missionaries with a series of questions: Why are you so enthusiastic about making Japanese people into Christians? Why do the daimyo you convert to Christianity destroy shrines and temples? Why do you eat cows and horses even though they are beneficial to humans? And why do you buy Japanese people and take them abroad as slaves? These growing doubts about Christianity were violently underlined in 1596, with what’s now known as the San Felipe Incident.

***

The San Felipe was a Spanish galleon, sailing under the command of Matías de Landecho. It was shipwrecked off the coast of Shikoku, one of the four main Japanese islands. Local samurai seized the cargo over Landecho’s protests. He was told that, if he had a problem, he needed to talk to Toyotomi about it. This is when, according to records, the ship’s pilot, Francisco de Olandia, showed Toyotomi’s staff a map of the world, highlighting the breadth of the Spanish Empire – all the territory it dominated. It’s difficult to confirm the nuances of a conversation which took place centuries ago, but the conclusion the Japanese drew from it were that missionaries were part of how the Spanish expanded their Empire, that their function was to weaken a country before it was invaded and conquered.

Now, there are full textbooks to be written about the relationship between religion and colonialism, about the sometimes unsavory symbiosis between churches and empires; we don’t want to cheapen that complex topic by making a snap judgment on the ultimate truth of this boast made by this Spanish pilot and what it implies about the motives of Francis Xavier. What is most important to this story is that Toyotomi Hideyoshi had ample reason to find it plausible, and that, in this delicate international situation, Francisco de Olandia had just made a politically disastrous maneuver.

The Japanese were not intimidated. Instead, they turned decisively against the small foothold Christianity had made on their islands. Laws were passed against practicing the religion, 137 churches were burned or destroyed, and 26 Christians in Nagasaki were martyred.

The Jesuits were ordered to leave Japan. A document ordering this purge in 1587 is still preserved today. Some of the Jesuits left with great public ceremony; but some remained behind in secret, tending to their congregations. And with each passing year, the danger of their mission grew. Once greeted with suspicion, then welcomed with a cautious open mind, Christians in Japan were now hunted and persecuted. The 16th century there is often referred to as “The Christian Century”, because of this dramatic rise and fall.

Toyotomi died in 1598, and in 1601 his successor, Tokugawa Ieyasu, finally achieved the dream of unifying Japan under one ruler. After defeating an army nearly twice the size of his, he was named Shogun – the Supreme Military Commander. It is one of the most important moments in Japanese history, and the Tokugawa Shogunate ruled the nation for the next two and a half centuries.

Tokugawa was willing to maintain some relationships with European powers – he struck a trade agreement with the Dutch East India Company, and frequently consulted with an English shipwright named William Adams. But he shared his predecessor’s concern that missionaries preaching Christianity could be part of a plan of conquest from Spain or Portugal. In 1614, he outlawed Christianity completely.

***

PART TWO

The largest rebellion in Japanese history was, in part, a Christian one. And its leader was a 16-year-old boy named Amakusa Shirō Tokisada. His story exists much more in legend then in documented history; and as such, how we characterize it depends strongly on who’s telling it. Some describe him as “The Child of Heaven”, blessed with miraculous powers and leading a war for the one true God; a kind of Japanese Joan of Arc. To others, he was an unrelenting radical, spreading death and discord.

Other than, quote, “some brief, imprecise references in official reports,” we don’t have any records of the actual young man. It’s strongly believed that he came from a Christian samurai family, that he was devoted to his faith, and that his Christian name was either Jerome or Francisco. But the rebellion he’s credited with was very real – 37,000 Christians rising up against the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1637. It’s called the Shimabara Rebellion.

But this is where we have to be careful not to oversimplify this event as a purely religious one. Not everyone who participated did so because of Christianity. For many, it was an economic revolt from the peasant class. Already overworked, overtaxed, and with nearly all the fruits of their labor going to wealthy landowners, their discontent turned into open hostility after a punishing new financial levy was handed down in the summer of 1637.

It stands to reason that, politically, the Shogunate would see an advantage in drawing attention away from their exploitation of the poor by painting the conflict as purely one of foreign-backed zealots undermining the nation. And the rebellion’s leader, Amakusa Shirō, seemed to play into that role.

Here’s what history tells us. Shimabara is in the south of Japan, to the east of Nagasaki. Amakusa was the name for the series of islands off the coast next to Shimabara. At the time of the rebellion, they had a significant Christian population. Facing famine and unending repression by their government, they rebelled against their daimyo. They soon found allies – what are known as ronin, samurai without masters to serve; as well as other samurai from Christian families nearby. On December 17, 1637, this rebel force rose up and killed the tax collectors, and then laid siege to Tomioka and Hondo castles. There, they were confronted by the armies of the Shogun’s allies; and, fearing that their disorganized force would fail in open combat, they retreated across a strait to the former site of Hara Castle. Breaking down the boats they had used to cross the water, they took the wood and fortified the remains.

The Shogun’s armies surrounded the castle and laid siege. This rebel force, which had grown to 37,000, now faced 120,000 trained and disciplined warriors. The Shogunate was taking no chances – they asked for cannons and gunpowder from the Dutch, bombarding the wooden fortifications. But Amakusa Shirō’s forces held firm for months, and succeeded in killing thousands of the Shogun’s forces. They weren’t equipped to last forever under siege, though; and by April, they were out of gunpowder, and out of food. On April 12, 1638, the Shogun’s forces breached the castle in a full-frontal assault; and after three days of fighting, the rebel force was vanquished. Rebels who survived the battle were decapitated. So were any citizens of Shimabara or Amakusa who were suspected of sympathizing with the rebels. Amakusa Shirō was likewise beheaded, and his head was put on display in Nagasaki as a warning to others.

Portuguese merchants were driven from the country – by 1639 an edict from the Shogun forbid the Portuguese from ever entering Japan again. A Portuguese ship sent to Nagasaki in 1640 to ask the Shogunate to reconsider the ban was burned, its crew and envoys executed.

And Christianity, taking the blame for the whole conflict, was driven even further underground. The Christian religion has many stories of martyrs – of people who gave everything for their faith. The story of Amakusa Shirō is rarely told among those stories, though; perhaps because we know so little about him; but perhaps also because there’s no silver lining to his actions, no renewal of faith brought on by his sacrifice. Indeed, after Shimabara, many Japanese Christians abandoned the faith.

Not only had the Shogun triumphed militarily, he had slaughtered much of the remaining Christian community in his country, and successfully orchestrated the justification to continue repressing and persecuting the religion and everyone who practiced it. Japan entered a long period of isolationism, of withdrawing from almost any contact with the outside world. And if there was any Christianity on the island, it existed only in pockets.

Amakusa Shirō has become a figure of folklore in Japan, most often as a villain. The Shimabara Rebellion was re-enacted in a series of Kabuki and Bunraku plays called “Kirishitan mono” (“Christian plays”). Given the violent dominance of the Tokugawa Shogunate, depicting the young rebel who worshipped an outlawed God as anything but a villain would have been a dangerous undertaking.

To this day, he appears in Japanese culture, even in a popular video game, in which he renounces God over his failed rebellion, turns to worship Satan, and raises a demonic army from the dead. Interestingly, his first appearance in a Japanese movie happened in 1962; at this time, when Japanese students were rebelling against conservative authorities, this film re-cast him as a tragic hero, an oppressed activist smothered by the state. With so little evidence to reveal the reality of this young man to us, he survives as a symbol in ongoing debates about freedom and faith, a name to be invoked because of the immense gravity of the battle he helped instigate long ago.

***

During the centuries after Shimabara, the Shogunate had a special group of samurai whose job was to investigate, root out, and destroy any sign of Christianity. But even without missionaries to guide them, some Japanese Christians carried on, and developed ways to hide their faith. They became known as kakure Kirishitan – hidden Christians. It was too dangerous to keep a Bible; or even to write down any records of their faith. So it became a religion of oral tradition, stories repeated and passed down from generation to generation. They created artwork that would secretly signal their faith – a statue of Buddha with a crucifix hidden on the bottom; or an image of Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of Mercy, made with secret iconography that, if you knew what to look for, would signal that it was actually an image of Mary, the mother of Jesus.

What happens to a religion after hundreds of years of only being practiced by word of mouth? Remember, there had already been an enormous language barrier just to introduce Christian stories and concepts in Japan. Now that they were on their own, practicing in whispers; what was it evolving into?

To understand what happened next, we need to talk about the Emperor – the Son of Heaven, the divine head of the Shinto religion, the traditional ruler of Japan who sits on the Chrysanthemum Thone. To this day, Japan has an Emperor – the current one is His Majesty Naruhito, the 126th Emperor, who ascended to the throne on May 1st, 2019 after his father abdicated. His role is almost completely ceremonial, but the line of Emperors he represents goes at least as far back as the 5th century, and possibly for hundreds of years before that.

The position of Emperor has meant many different things throughout that long history – sometimes an all-powerful ruler, sometimes a figurehead providing legitimacy to a military shogun. The Shogun had been effectively more powerful than the Emperor for a period of nearly seven centuries; until a series of events now known as the Meiji Restoration.

In 1853, a fleet of American Naval vessels led by Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Edo Bay, now known as Tokyo Bay. What Perry found was a nation that, after two centuries cut off from the outside world, had fallen far behind in industry and technology. The Tokugawa Shogunate had succeeded in stamping out threats to its power, in extracting uncountable wealth from the peasants of Japan; but it had failed to advance its civilization. Commodore Perry was there to open up trade negotiations – the overwhelming power of his Navy, which the Japanese called “The Black Ships”, assured that those trade deals were immensely one-sided.

The outside world had returned to Japan, and so had Christian missionaries. And when the Japanese people realized that they had been weakened by their rulers, and made ripe for exploitation by foreigners, a movement arose that ended the power of the Shogunate, and restored the Emperor as the true head of state, with the daimyo loyal to him forming a new government. And the new Constitution shepherded by Emperor Meiji actually provided for some limited freedom of religion.

As missionaries returned, they were shocked to encounter the kakure Kirishitan – the descendants of Christians who had been practicing in secret for over two hundred years. In 1865, a group of fifteen Japanese peasants approached Bernard Petitjean, the first European Christian missionary in Nagasaki since 1614, telling him, “Our hearts are the same as yours.” They expressed a fervent desire to see religious artwork, depicting Mary and Jesus.

Petitjean and the other missionaries quickly learned that, after generations of isolation and oral storytelling, the Japanese understood Christianity very differently. They had a Holy Trinity, but without a Holy Spirit – remember, that in Japan, there are almost infinite spirits, occupying everything. Their Trinity was the Father, the Son, and the Mother – the Virgin Mary assuming a place equal to God and Jesus. The kakure Kirishitan had come to believe that Mary was an incarnation of the Buddha Avalokiteshvara – the Bodhisattva of Compassion. The current Dalai Lama, by the way, is considered to be another incarnation of this same spirit. And in Japan’s belief, Jesus’s time on Earth didn’t end with crucifixion, he spent forty days afterward teaching, and then went on to fight many battles to defend his followers.

You can see how the history of Japan’s Christians, the violent repression, and the importance of keeping the lessons of their faith alive, may have woven itself into the stories they shared about Jesus. Much in the way that animals isolated on the Galapagos Islands took on unique forms which Charles Darwin studied to develop his theory of evolution; Christianity, when isolated on the islands of Japan, evolved in its own unique way.

PART THREE

Now that we’ve packed this knowledge with us, let’s make our pilgrimage to the little town of Shingō, and the burial mounds where, the locals will tell you with absolute faith and certainty, Jesus and his brother are buried. That’s right, I said brother. Actually, it’s not even all of Jesus’s brother. Just his ear.

Much of this story comes from a set of papers known as the Takenouchi Documents. They were reputedly several hundred years old, but we can’t do anything to verify this because, after they were discovered in 1936, they were supposedly destroyed during World War II. The Museum in Shingō has what they describe as reproductions of these documents, but the consensus among scholars is that they aren’t authentic – they’re either a hoax or a sincere effort that doesn’t rise to the level of grounded history. And yet there are details to see and experience in Shingō which confound attempts to dismiss the whole story as a tourist fabrication.

It’s worth remembering at this point that, even in the approved books of the Bible, there are massive gaps in the life of Jesus. Only the Gospels of Matthew and Luke describe his infancy; it’s from those books that we get the story of his birth in Bethlehem, his family’s travel to Egypt, and his later return to Judea. Only one incident of his childhood is told – a single incident in a temple when he is around twelve; and then the story jumps forward to the beginning of his public ministry, by which time he is thirty.

What happened in those missing years is open to speculation; and there are many traditional beliefs. Some assert that he traveled to India; others that he went back to Egypt. Others say that he simply stayed in Bethlehem, became a carpenter, and lived quietly until 30. The Takenouchi Documents tell a different story, though. They say that, during those missing years, Jesus journeyed through Asia, and spent ten years in Japan, studying theology, before taking those lessons with him to Judea to begin his ministry. As it is in the Bible, his teachings and the crowds they inspired were a threat to the ruling powers, which conspired to kill him.

But in this version, Jesus escapes crucifixion. Instead, the Romans crucify his brother, James. Then, Jesus took a lock of his mother’s hair, and an ear from James’s body, and began a long journey back to Japan; where he ended up in Shingō village. There, he lived a simple life as a teacher, adopting the name Daitenku Taro Jurai. He married a local woman, fathered three children, and lived to the age of 106; before passing away and being buried next to his brother’s ear. Opposite the earthen mounds marking their final resting place are the tombs of the Sawaguchi family, allegedly Jesus’ Japanese descendants. And here’s one of those details that make this story all the more interesting – the Sawaguchi family crest incorporates a Star of David, the six-pointed shape recognized around the world for indicating Jewish identity.

Every year in Japan, usually in late August or early September, is the Buddhist Festival of Obon – like Día de Los Muertos, it’s a holiday to celebrate the dead, especially your ancestors who have passed on. There are many wonderful traditions associated with Obon, but in Shingō, there’s one tradition which happens nowhere else in Japan. The locals sing a song called “Nanyada” – the lyrics aren’t in Japanese, in fact, they’re basically nonsense. But Theology Professor Eiji Kawamorita has studied these lyrics, and believes there’s a case to be made that these supposed nonsense words are actually a corrupted form of Hebrew. Kawamorita believes that you can trace the lyrics of “Nanyada” back to a Hebrew phrase meaning “We praise your Holy Name.” But how could this be possible?

The people in and around Shingō village are quick to point out local variations in speech, custom, belief, behavior; even differences in eye color and physical appearance that distinguish them from the residents of nearby villages. They claim that the source of these differences traces back to those descendants of Jesus marrying within the community – effectively making every resident there, the offspring of Christ.

Now, are these differences significant enough that you could make a genetic study of them? Probably not – the thought of being descended from the Messiah might simply make a person in an isolated community unconsciously likely to exaggerate small details.

And there’s one fairly glaring fact which makes the story of Shingō Village vulnerable to scrutiny – the so-called grave of Jesus is marked by a cross. Locals claim that the crosses have been there since before the arrival of the original Jesuit missionaries; but this raises significant questions. In Jesus’s time, the cross wasn’t a symbol of his ministry, it was an instrument of Roman torture and murder. The Bible says nothing about his tomb being marked with a cross; there was no burial tradition connected to crosses. The Christian Church didn’t even begin to use the cross as a symbol until at least the fourth or fifth century, hundreds of years after the story told in the Takenouchi Documents. And if, as claimed in these documents, Jesus was never crucified, why would the cross become a symbol at all?

The historical record just doesn’t give us enough to draw any conclusions about what happened in Shingō, how this story took root; but if we look back on what we know about Christianity in Japan, it’s possible to formulate a couple of plausible theories.

It’s quite possible that, centuries ago, a European shipwrecked near Shingō, was sheltered by the locals, and fathered children there. Or it’s also possible that, even as missionaries were being expelled by the Tokugawa Shogunate, one chose to stay behind, hiding in this isolated place. And in the centuries after, as the kakure Kirishitan practiced their faith in secret, with oral storytelling the only safe way to talk about Jesus, it’s quite plausible that the stories of Jesus, and the stories of their local teacher and missionary, started to overlap with each new generation. Remember how vast the language and culture gap is, and how the Japanese created their own ideas about concepts like the Holy Trinity. Isn’t it possible that they could see one of God’s emissaries on Earth as, effectively, the same thing as God?

PART FOUR

The Christian religion is filled with stories of faith tested by trial, of people who suffer but endure in their belief that salvation awaits them. “Why would you let this happen? Why would you do this to me?” is a question that many pose to the Almighty in Biblical stories when they are tested. There’s a final story to tell on this subject which, I have to admit, leaves me shaken.

Remember when I said that, when the Jesuits first established themselves in Japan, that they did so in Nagasaki, that the port town became the center of Christianity in Japan? That remained so even during the years of the hidden Christians, worshipping in secret. And it was still true on August 9th, 1945, when the American Army Air Force B-29 Bomber known as Bock’s Car dropped an atomic bomb on the city, our second nuclear attack on Japan after the bombing of Hiroshima three days before.

Nagasaki wasn’t the designated target that day. The plutonium bomb, nicknamed “Fat Man”, was supposed to be detonated over the city of Kokura; but cloud cover and thick smoke from other bombing campaigns made it impossible for the crew of Bock’s Car to find their primary target. Nagasaki was their backup; and after changing course, they found that it, too, was obscured by cloud cover. But just before they were set to turn back; the clouds parted, and bombardier Captain Kermit K. Beahan announced that he could see a viable target, and Fat Man was dropped.

In his excitement, though, he had failed to account for the effect of the wind; and the atomic bomb drifted. It didn’t hit the military target - the Mitsubishi factories at the port on the edge of town. Instead, it exploded 1,650 off the ground, directly over Immaculate Conception Cathedral, the largest Roman Catholic Church in Japan. Of the 100,000 people who died in Nagasaki from the atomic bomb, 10,000 were Japanese Christians.

The combination of circumstances that leads to a moment like this is so far beyond unlikely; it’s the sort of impossibility that people will unconsciously describe as “miraculous”. But that seems like an obscene way to describe this – what’s the opposite of a miracle?

There aren’t many Christians on Earth who have had to carry their faith along a darker path than the Japanese Christians. The Christians of Nagasaki saw themselves as God’s chosen people in their nation, and understandably wondered how it is, in the face of that, that so many of them were taken in the horror of nuclear fire.

A 2003 article in the New York Times described how many of the traditions of the kakure kirishitan are vanishing as older generations pass along. In a way, it makes sense, they no longer need to fear torture or execution for their beliefs. Oral storytelling was a way to keep faith alive when owning a Bible could mean death. Does it still have a purpose now? In that Times article, the 85-year old pastor of a kakure Kirishitan church in a rural village outside Nagasaki is quoted as saying “I am worried about the future. I am not sure it will last.”

There’s some elusive connection between the resilient, often extraordinary methods that Japanese Christians evolved, and those burial mounds far up in the mountains in Shingō. The stories they tell are, if we apply a few strict questions of history, impossible. And yet the power of those stories has affected the course of history. Faith remains a great and powerful mystery, one that can defy and sometimes even thwart facts and study. It’s a rich subject to contemplate, whether you’re deep in the beautiful Japanese woods, or at home for the holidays. Relish them as you celebrate them – they worked hard to get here.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Evadne Hendrix; and our creative director is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by Kevin Wetmore. Our Senior Story Editor is Nicholas Thurkettle, and our fact-checker Nicholas Abraham; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.