Episode 15: Frankenstein and the Pacemaker - How Science and Fiction Saved Lives

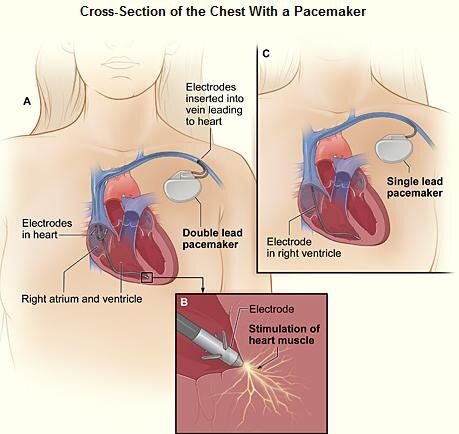

When the beating of the heart becomes irregular, or when it begins to fail because of age or damage from a heart attack, we’ve developed this miraculous device for getting the heartbeat back to normal – the artificial pacemaker. It’s considered one of the most life-changing inventions of 20th-century medicine.

So where did the idea of using an artificial electrical impulse to control the heartbeat begin? Well, as with most scientific progress, there’s a long chain of contributors, but I want to talk today about a transformational role played by an inquisitive man from Minneapolis, Minnesota named Earl Bakken; and the inspiration he got from a movie he saw when he was just a little boy.

Listen to learn more about:

How Mary Shelley's Frankenstein influenced the invention of the pacemaker

The Life of Mary Shelley and the circumstances that lead to her writing Frankenstein

Earl Bakken and his life

How Earl Bakken and other scientists invented the pacemaker

The first battery and how it was invented

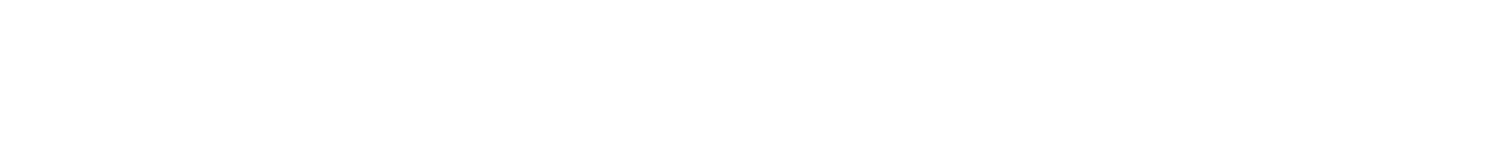

Lake Geneva

Geneva Lake in Switzerland

Photo taken by MF Thomas

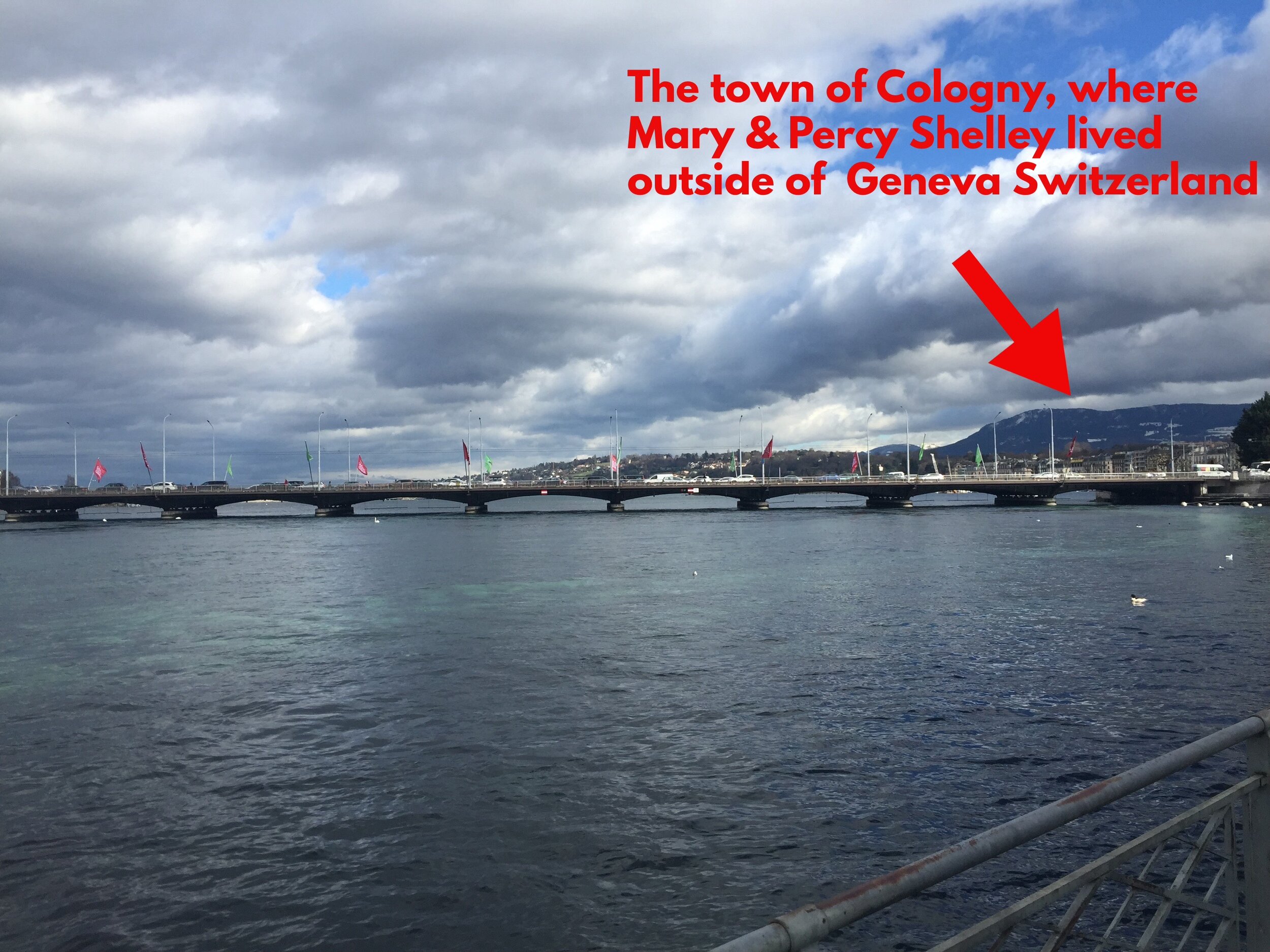

Pacemaker X-Ray

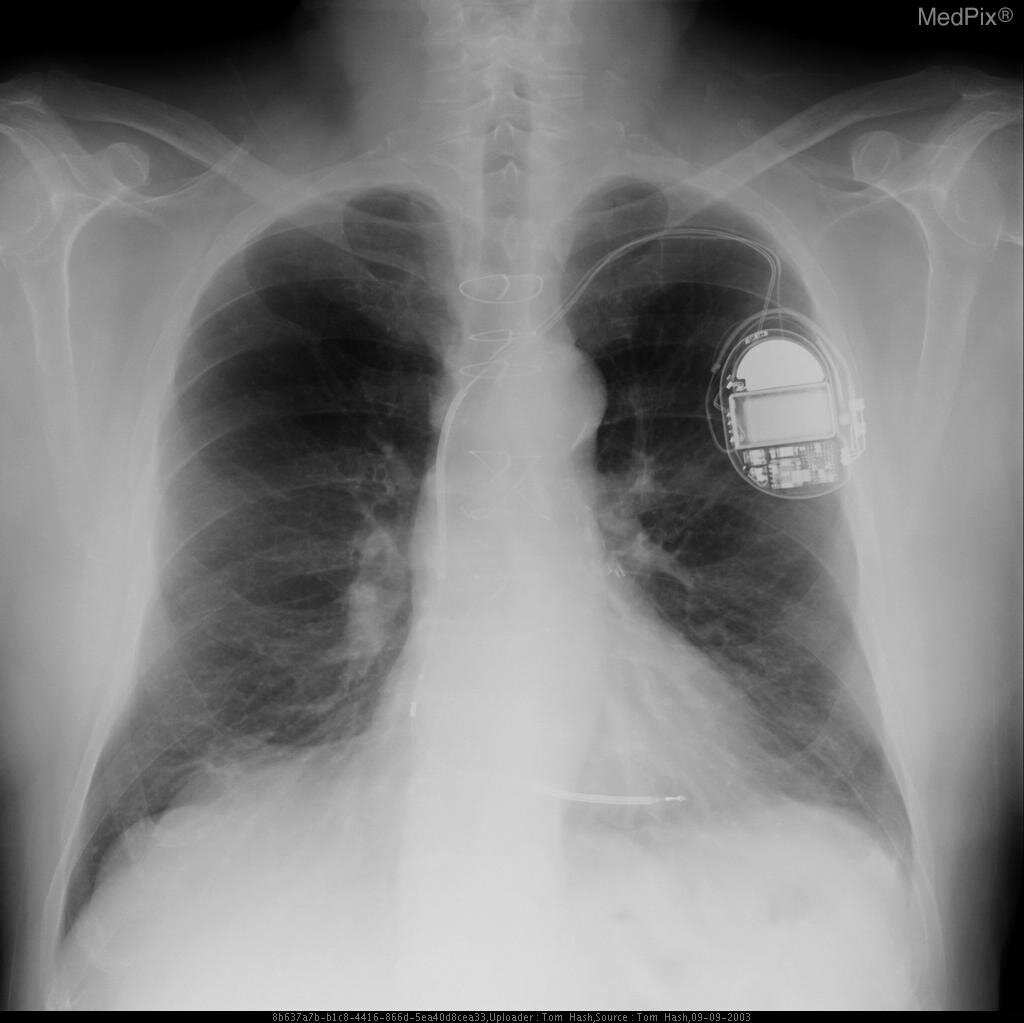

First Battery

Mary Shelley

Byron Phillips

Portrait of Percy Shelly

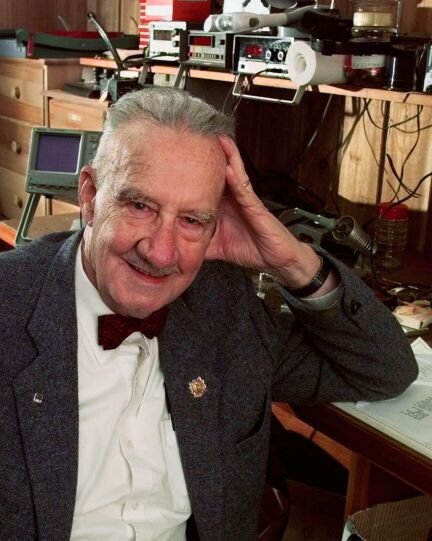

Earl Bakken

Pacemaker Diagram

The Necessity of Atheism

Alessandro Volta

Frankenstien's Monster

Prometheus

Wilson Greatbatch

St. Pancras Old Church where Mary Shelly's mother is buried

Mount Tambora

Lake Geneva

The Bakken Museum

The Bakken Musum

Frankenstein's Laboratory at The Bakken Museum

Mary and Her Monster exhibit at The Bakken Museum

Sources

REFERENCES/ADDITIONAL READING:

Tufts Now: Think you know your Frankenstein?

Thought Co: Frankenstein Themes, Symbols, and Literary Devices

New York Times: Earl E Bakken Obituary

Eetimes: Pacemaker was born of a blackout

Csoonline: What are the security implications of Elon Musk’s neuralink?

NBC News: Elon Musk’s Neuralink puts Chips in Pigs Brains

Edu News: Remembering Earl Bakken

Sickness in Time by MF Thomas Podcast

Killafornia Dreaming Podcast by Roseanne Sinclair

MUSIC:

Chemical Chains by Empyreal Glow

Parliament’s Crisis by Cody Martin

Pins and Needles by Tide Electric

Weeping Toothcrust by Isaac Joel

Perfect Spades by Third Age, Nu Alkemi$t

IMAGES: All used under Creative Commons Licenses

Full Script

At any given time, approximately 3 million people around the world are walking around with a battery-operated device, no large than a matchbook, no heavier than 2 ounces, implanted in their chests. It sits just below their left collarbone, and it’s there to help keep the electrical system of the human heart going when the natural system begins to give out. It’s called the pacemaker.

Every animal has a heartbeat. It’s created when the muscles in the heart contract. You can feel it, and if you listen close, you can hear it. It’s the first thing we check to see if something is alive or dead. Those contractions in the heart muscle originate with electrical impulses that are called action potentials. Our hearts are driven by electricity in the same way that pistons drive a motor.

The cells that generate these electrical impulses are known as pacemaker cells, and they are in charge of how fast our hearts beat. This is our body’s natural way of keeping our heart pumping, our blood flowing, and our bodies alive.

When the beating of that heart becomes irregular, or when it begins to fail because of age or damage from a heart attack, we’ve developed this miraculous device for getting the heartbeat back to normal – the artificial pacemaker. It’s considered one of the most life-changing inventions of 20th-century medicine.

So where did the idea of using an artificial electrical impulse to control the heartbeat begin? Well, as with most scientific progress, there’s a long chain of contributors, but I want to talk today about a transformational role played by an inquisitive man from Minneapolis, Minnesota named Earl Bakken; and the inspiration he got from a movie he saw when he was just a little boy.

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 15: Frankenstein and the Pacemaker – How Science and Fiction Saved Lives.

PART ONE

Earl Bakken was born January 10th, 1924. Although he had a sister, she was eighteen years younger, and Earl essentially lived the life of an only child. And from what we know, his parents surrounded him with just the right amount of attention and love to help him thrive.

From a very early age, Earl was fascinated by anything electrical in the house. He spent countless hours fiddling with the components of electrical devices and experimenting with batteries. Before long, he had built a robot out of an Erector set that could smoke a cigarette and brandish a knife. He dismantled his parents’ radio, he ran phone lines from his house to his friend’s house across the street; nothing was off limits.

When he got older, he even tried to invent a machine he named the Kiss-o-Meter; in theory it would calculate the strength of one’s feelings when kissing. If he had been able to make that work, it would certainly have changed the world.

While some parents would have been terrified to see their child playing with electricity, Earl’s mother not only allowed him to indulge in all the tinkering his heart desired, she encouraged it.

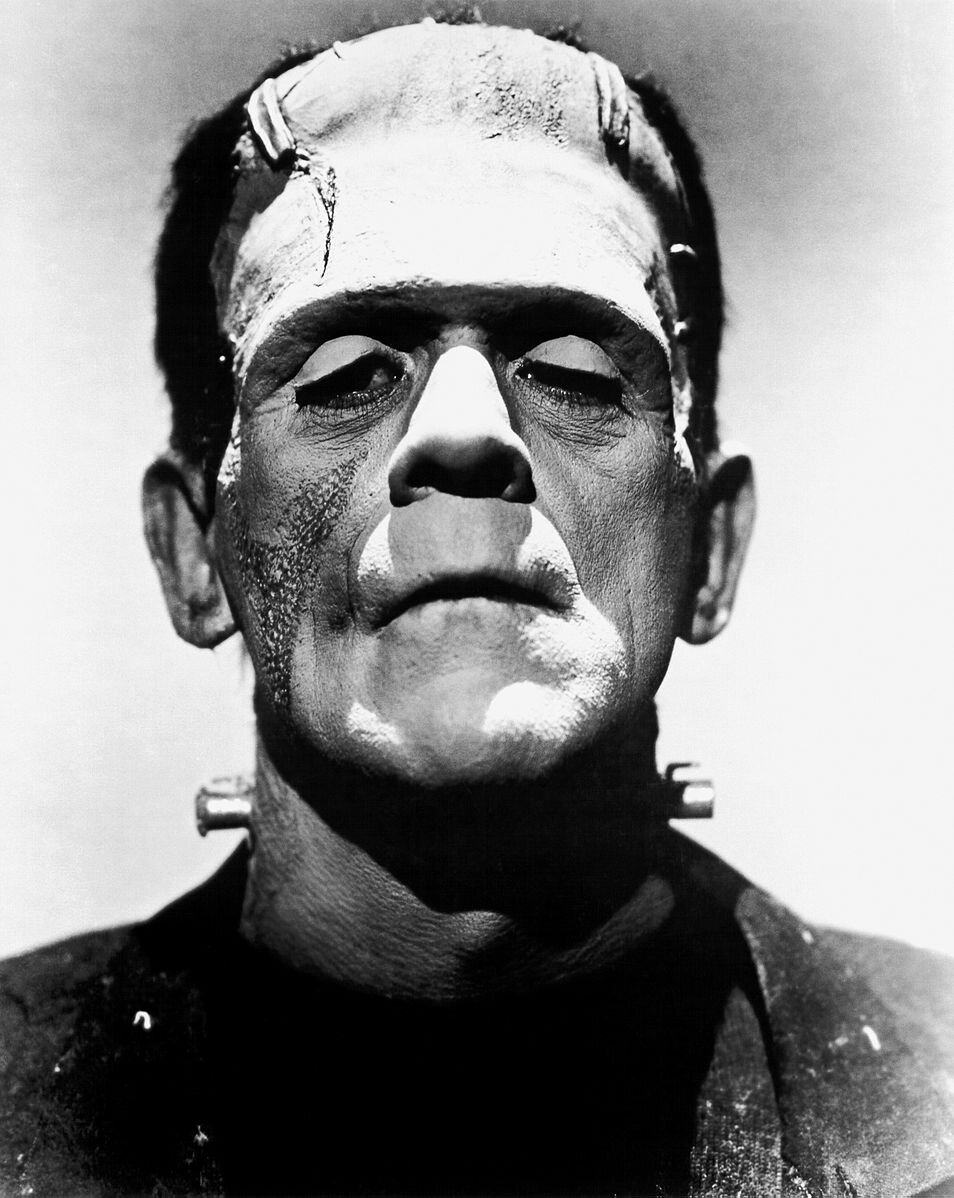

In 1931 when Earl was 7 years old, he was taken to a local movie theater to see a brand-new film based on a famous book – Frankenstein. The legendary film starring Boris Karloff made many changes from Mary Shelley’s 1818 book; but, of course, young Earl knew nothing of that.

What he saw in the movie was the scientist, Dr. Frankenstein, building a creature out of the parts of dead bodies. The creature is placed on a platform, which is raised towards the roof of his lab. The roof opens up and outside, there is a thunderstorm. A bolt of lightning provides the essential electric charge. The platform descends back into the laboratory, where the Doctor sees his creation’s hand begin to twitch. In feverish triumph he screams “It’s alive! It’s alive!”

Something else was alive at that moment in young Earl Bakken – the idea that electricity wasn’t just a force for toys and gadgets. It could be the power of life itself. That idea stayed with Earl for the rest of his life, and helped inspire the breakthrough he made many years later.

We’ll discuss the circumstances of his invention in a bit, but first, it’s well worth it to take a closer look at Frankenstein’s creator, Mary Shelley, to see how her life story is bound up in the fictional story that immortalized her name. Like Dr. Frankenstein himself, she made something out of death, something extraordinary and frightening, and the consequences of her act of creation followed her until the end of her days.

PART TWO

There’s an ongoing debate over what to call the creature stitched together from stolen corpses in the novel Frankenstein – the book’s full title, by the way, is Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. It never receives a proper name, and is usually referred to as “Frankenstein’s Monster” or “The Creature”. In the book, it learns to speak, and when it confronts its creator, it laments,

“Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel.” This Biblical reference demonstrates to the Doctor the consequences of playing God – he succeeded in creating life, but then rejected and abandoned the life he created. There’s a 2017 novel by Theodora Goss called The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter which reimagines various 19th century characters, including Dr. Frankenstein’s creation. In her book, Goss gives the creature the name of Adam.

Although it’s considered one of the pioneering works of sci-fi and horror, there’s so much more going on in Mary Shelley’s novel, themes that still resonate over 200 years later – morality, human nature, natural laws, alienation, prejudice, and the ethics of pursuing scientific knowledge. It doesn’t take long to see the many connections between the themes of the book, and the life of tragedy and rebellion she led.

Mary was born on August 30, 1797, in London, to William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft; both of them prolific and celebrated writers and progressive activists. But in a horrible turn of events, Mary’s mother became sick from an infection while giving birth; and died just ten days later. People who knew her mother would tell Mary how beautiful she had been, and how strong the resemblance was both in her looks and her temperament. So young Mary was haunted her whole life by the mother she never knew; and the thought that she was some kind of copy, born out of her mother’s death.

When Mary was 4, her father re-married, to a woman named Jane Clairmont. Jane had two children of their own, and brought them into the new combined household. Little Mary started showing signs of alienation and loneliness; the feelings only got more intense when William and Jane had a child of their own. She became more and more withdrawn, more detached, and the clear connection between her emotional state and her father’s new marriage created a deep rift between them. In addition, William’s publishing house was deeply in debt, and he often needed loans and charity from colleagues to stay out of debtors’ prison.

The more Mary grew, the more her appearance and mannerisms resembled her mother’s. She was such a strong, living reminder, that her step-mother Jane began to develop feelings of resentment towards her. Mary was sent away to stay with a family friend in Scotland.

Later in life, Mary wrote of her time in Scotland as a “blank and dreary” period in her youth. But what was born of that desolate time, when her days and nights were long, lonely, and dull, were the beginnings of Mary’s writing. Although she had very little formal schooling, her father had tutored her extensively, and she had spent her whole life around the poets and politicians and scholars he knew. With her life void of so many things - love, family, affection, companionship; she used her imagination to fill in those empty spaces.

***

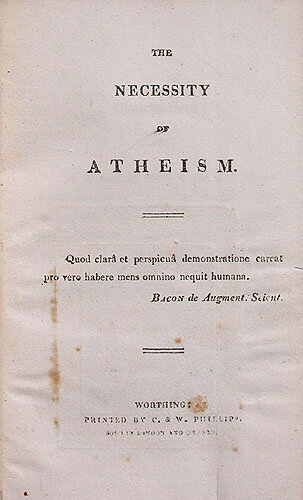

In 1812, Mary traveled back to England to visit her father. While she had been away, her father had taken an aspiring young poet under his wing. His name was Percy Shelly. The son of a politician, Percy had grown up feeling like he didn’t fit in. Bullied at the prestigious academy where he had studied, he suffered from intense nightmares and bouts of sleepwalking. He had brilliant language skills but seemingly common tastes – instead of the classics, he preferred reading mysteries, romances, and ghost stories. He carried on dangerous home experiments with acid and gunpowder; one such experiment blew up a fence at his school. Later, he was expelled from Oxford for writing an anonymous pamphlet known as The Necessity of Atheism.

Mary Shelley was just 15. Percy was 20, and married to a schoolmate named Harriet. Nevertheless, Percy and Mary’s first encounter was intense, they sensed a powerful kinship with one another. They both remembered it even as Mary returned to Scotland.

In the spring of 1814, Mary returned to England; and Percy was still there. He’d grown closer to the family, even helping settle her father’s debts. But his marriage to Harriet had become estranged. Not long after Mary arrived, their attraction to each other became undeniable. When they declared their love for each other, it was in the graveyard of the St. Pancras Old Church, standing over the memorial for her mother. Mary was just 16.

Percy abandoned his wife Harriet, and took Mary with him to Europe to travel and explore. Young Harriet had been willing to abandon her family and her fortune to be with Percy Shelley, and now she was alone, and devastated. And William Godwin was furious that his star pupil Percy had run away with his daughter. Mary’s relationship with her father never recovered.

It’s important as we talk about all of this to discuss the Romantic movement. At this time in European history, there was an intense cultural focus on emotions, on individual joy, on an appreciation of the natural world, and a celebration of the past. This Romantic philosophy was woven deeply into education, social sciences, and the arts. The Industrial Revolution had viscerally transformed the surrounding world – creating wealth and opportunity and extraordinary scientific progress, but with an ugly cost – gouged and scoured countrysides, black pollution in the air, individuals reduced to numbers in a ledger, serving the almighty production quota. Romanticism was the effort to rage against this, to elevate the importance of chasing your own loves and ambitions, even if it defied the social order.

Mary took Percy’s last name, and became Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. But they determined to live in an open relationship bound by their passion for one another. It was an intoxicating theory, but in practice, it caused constant instability. It has long been suspected that Percy had an affair with Mary’s step-sister; and that they even had a baby together.

But any fights or transgressions did nothing to diminish the passion Mary and Percy had for each other. They were romantics, they were radicals, and they were writers, and they supported each other’s ambitions fully.

***

In 1815, Mary and Percy had their first child - a daughter. But she was born prematurely, and died in just two weeks. It was a sickening echo of the tragedy of Mary’s own birth. But they continued working to start a family. The following year, she gave birth a second time to a boy; she named him after her father, William. The world he was born into was a much harder one than anyone could have predicted; all because of a volcano, half a world away.

The worst recorded volcanic eruption of the 19th century came from Mount Tambora in Indonesia. Before the eruption, it was one of the highest peaks in the Indonesian island chain – 14,100 feet high. Today, its elevation is just 9,350 feet. The eruption was so powerful that nearly a third of the mountain was blown into the earth’s atmosphere – 12 cubic miles of gases, dust, and rock. 10,000 people living on the islands were killed almost instantly.

But the devastation did not stop there. There were tsunamis, raining ash, and the pollution in the atmosphere spread all over the world. An unnatural cold swept through Europe and North America, as dark pollution blotted out the sun. Some scientists now refer to it as a micro-Ice Age. Crops and livestock suffered irreparable harm; in America, farmers who had lived and worked in New England started heading west, seeking better weather. And the damage to farming all over the world created devastating famine.

It was in the middle of this, in 1816, as the ashes from Tambora crept across European skies, that William was born. Looking for sanctuary from the suffering around them, Mary, Percy and baby William traveled with a group of friends to stay at Lake Geneva in Switzerland.

One of the friends staying there was the famous poet Lord Byron, and it was Byron who suggested a challenge to liven up their evenings – they would tell each other ghost stories, and compete to see who could create the most unique and interesting one. And it was the story told by Mary Shelley, then just 18 years old, based on a nightmare she’d had the night before, that was the clear winner, and became the basis of Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus.

If you don’t know the story of Prometheus; he was the Greek god of fire. His name means Forethinker; he was described in myth as an intellectual who eventually developed into a master craftsman, but was also known to be a trickster. He played a prank on the almighty Zeus, tricking him into taking an offering of bones and fat rather than the meat. Zeus was enraged, and as punishment for the trickery, he hid the element of fire from all mortals. But Prometheus took it from where it was hidden and gave fire back to the Earth. In retaliation, Zeus tied Prometheus to a cliff, where every day, birds would attack him and tear out his liver, killing him until he was revived the next morning to endure the torture again. Zeus also ordered the creation of Pandora, who opened a jar which released all the evils and diseases that plague humankind.

The message in these Greek myths was that claiming the power of the Gods always came with a cost; an idea at the heart of Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley set to work turning her ghost story into a novel; but tragedy continued to haunt her. One of her half-sisters, Fanny, took her own life. Just one month later, Percy Shelley’s wife Harriet also died by suicide, drowning herself in a lake in Hyde Park. She was just 21.

Mary Shelley was just 20 when she finished her novel; and it was published on New Year’s Day, in the year 1818. Through famine, broken relationships, and unimaginable grief, she had carried her work through to completion; a work that has become immortal.

While it would be comforting to imagine that this marked the end of the dark period in her life, this wouldn’t be the truth. Percy, battling deep depression of his own, continued to be reckless and selfish – losing custody of his children from Harriet, getting arrested for debts, having affairs. Mary had given birth again, to a daughter, Clara; but Clara died that September, having lived just one year. The following June, Mary’s son William died from malaria. Her next child, Percy Florence, would be the only one to survive into adulthood.

These long years of death had taken a brutal toll on both Mary and Percy Shelley. They had moved with friends to an isolated villa on the edge of a bay in Italy. Mary was lonely, describing the house as like a dungeon. In June of 1822, she suffered a violent miscarriage, and nearly died from the loss of blood. Percy placed her in a bathtub and covered her in ice before looking for a doctor; the doctor later confirmed that this saved her life.

Then, the ultimate tragedy. On July 1st, Percy went sailing with two companions. Their boat was overtaken by a fierce storm, and ten days later, their bodies washed ashore.

Mary Shelley had always been able to write through her suffering; but for all the ups and downs of her long affair with Percy, he had been the love of her life. The despair of his death kept her from working for five years.

By 1827, Mary was finally able to write to the best of her abilities once again, and she flourished as both an author and an editor. She helped build the legacy of both Percy and her father, William Godwin, editing and publishing some of their works. Her surviving son, Percy Florence, married a young woman that Mary loved deeply; and perhaps for the first time in her life, she had both love and stability around her. The second half of her life was likely happier, but far too short – Mary Shelley passed away at the age of 53 from a brain tumor.

After her death, many of her writings were discovered in her desk, along with some other artifacts that, while startling, seem wholly appropriate for someone with the imagination to create Frankenstein. She kept locks of hair from each of her children that passed away, as well as a small package that contained Percy’s cremated heart. She had wrapped his heart in a copy of one of his poems, an elegy he called Adonais.

Even during her lifetime, Frankenstein was Mary Shelley’s defining work. Astonishingly, the book was published anonymously at first, though Percy wrote a preface to give it some visibility. No single reason for this choice is given; but if their fear was that Mary’s work might be dismissed because of her gender, or her relationships with Percy or her father; those fears were realized in some of the early response.

Though the book was wildly popular, scholars speculated that it was really due to Percy’s work polishing up the musings of a teenage girl; or that she was a pretender to the literary legacy of her father. A prestigious quarterly journal called The British Critic considered the whole work unworthy of discussion because it was written by a woman, who shouldn’t be entertaining such ugly ideas.

Quote: “The writer of it is, we understand, a female; this is an aggravation of that which is the prevailing fault of the novel; but if our authoress can forget the gentleness of her sex, it is no reason why we should; and we shall therefore dismiss the novel without further comment.” End quote.

The British Critic stopped publishing in 1843. Frankenstein is still published all over the world.

PART THREE

It’s impossible to ignore the parallels between the themes of Frankenstein and the mixture of rash courage and horrible, haunting grief that filled Mary Shelley’s life. The novel doesn’t dwell long on the process of bringing a body to life with electricity; it’s more interested in deeply-felt emotions – Victor Frankenstein’s ambition and obsession, and his shameful rejection of his creation; the Creature’s loneliness, anger, and confusion, thrust into a world it doesn’t understand and which fears and judges him. They become trapped in a cycle of revenge, which ends up killing everyone Victor cares about, and finally, Victor himself. The book ends with the Creature mourning Victor’s death, and exiling himself on an ice floe near the North Pole, knowing that his crimes make him unfit to live among people.

Perhaps the monster she created represented a latent and incurable guilt. Mary’s own birth contributed to the death of her mother; her affair with Percy Shelley very likely contributed to Harriet Shelley’s suicide. Maybe it represented the way birth and death were inextricably linked in her mind, having lost all but one of her own children. And maybe it represented their attempt to create a life together defined by their romantic rejection of society, only to watch that life wreak havoc on those around them.

But behind all those feelings, those personal themes that Mary poured into the story, there was this idea, the concept of an electric spark bringing life back to dead tissue; the idea that was turned by Hollywood into a bolt of lightning, the idea that Earl Bakken eventually incorporated into his implantable pacemaker. Where did this come from? Thankfully, we have it in her own words.

In the preface of the 1831 edition of her book, which now proudly bore her name, she described that spring in Switzerland and the nightly storytelling sessions.

Quote: “Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others, the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.

“Night waned upon this talk, and even the witching hour had gone by, before we retired to rest. When I placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness far beyond the usual bounds of reverie. I saw - with shut eyes, but acute mental vision - I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.” End quote.

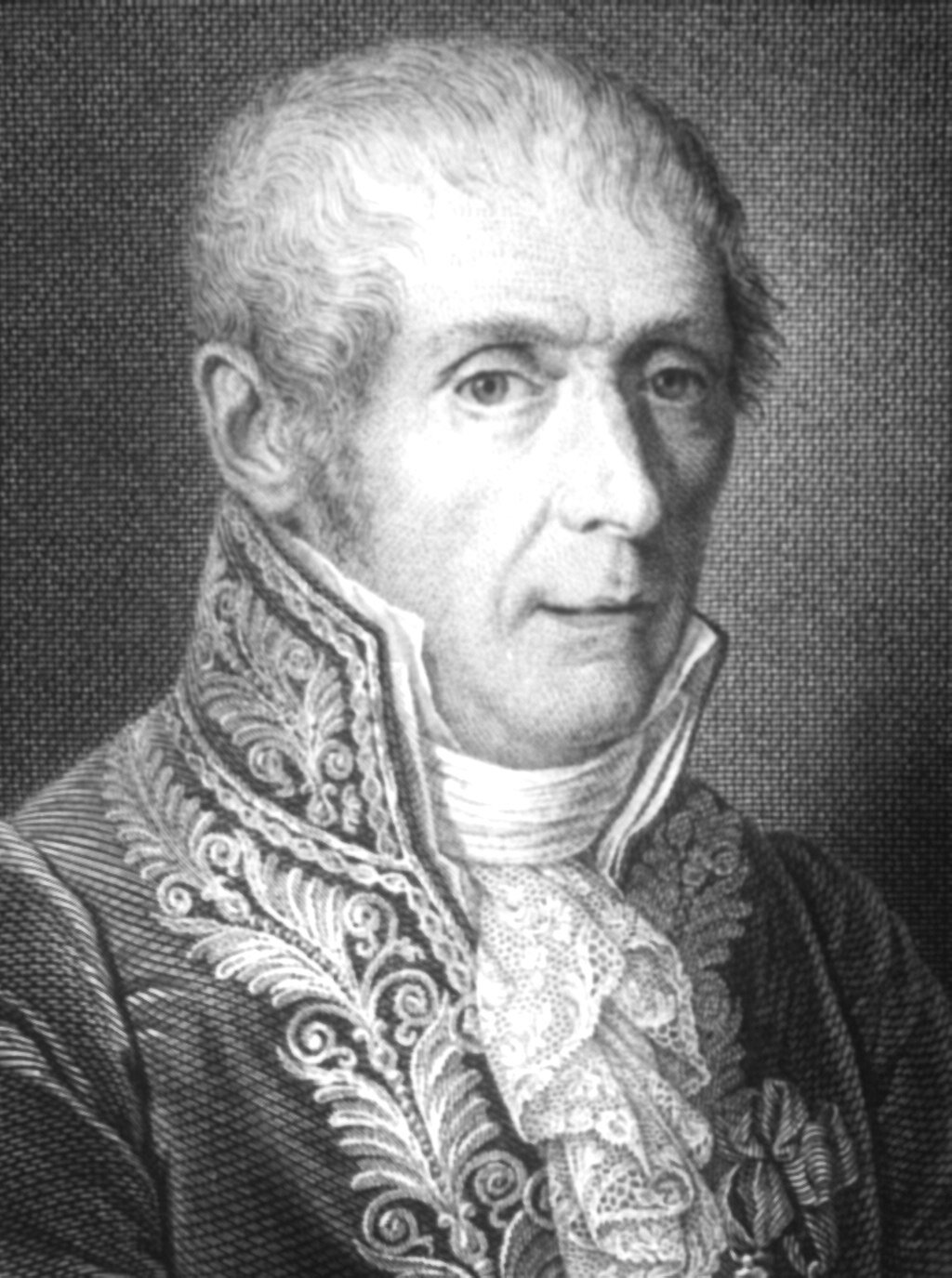

The word, galvanism, is the key here. It was coined by a real scientist, an Italian chemist and physicist named Alessandro Volta. If you noticed the last name, yes, Volta is the reason we call them “volts” of electricity. Scientists were big on naming things after themselves, and Volta used the term “galvanism” to describe the work of his colleague, Luigi Galvani. Galvani wasn’t just a physicist, he was a biologist and a philosopher. He was one of the very first to venture into the field of bioelectricity, and though he got a lot wrong, he laid the groundwork for a whole field of science, and for Mary Shelley’s creation of Frankenstein.

The reason Volta came up with the term Galvanism is because he was trying to prove his colleague’s theories wrong. Galvani had discovered he could trigger the muscles in a dead frog’s legs; and that there was an electrical current causing the movement. He intricately dissected the frogs so that the nerve endings and spinal cord were intact; he believed that the electricity was created by a chemical interaction inside the frog’s body; that there was literally an electrical fluid created in a living brain and carried through the bloodstream.

Volta disagreed; he didn’t think that the electricity was coming from a chemical interaction. He believed it was caused by the metal instruments Galvani was using.

Amazingly, he was so determined to prove Galvani’s theory was wrong that he invented a device of his own that could provide continual electrical power to a circuit. Today it’s known as the voltaic pile – the world’s first battery. An invention that Earl Bakken would certainly need later for his pacemaker.

This scientific debate was happening in the 1790’s, and it was truly radical for its time. Before this, the leading scientific theory was that muscles in the body moved by filling with air or fluid. Today, we call it the “balloonist theory”; and while it sounds faintly ridiculous now, that’s how science works – it makes a guess until new information allows you to make a better guess.

So the idea that we were powered by an electrical current we didn’t fully understand was working its way into the public consciousness, it was something that intellectuals like the Shelleys would have been aware of; and while Mary Shelley wasn’t a scientist herself, her ability to extrapolate from this cutting-edge idea with her rich imagination, to create a nightmare just plausible enough to feel compelling to her readers, is what separates great authors from the merely good.

PART FOUR

So let’s come back to young Earl Bakken, and the movie version of Frankenstein which he watched as a little boy, over a century after its original publication. Like the creature itself, it was a bit of a stitched-together imitation of her book, with many changes that became part of the popular image of the creature even though Shelley never wrote them, like the metal bolts on the Creature’s neck. In addition, in Boris Karloff’s first performance as the Creature, he doesn’t speak. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein eventually gains a full human vocabulary, and is eloquent in communicating his anguish.

Bakken didn’t know any of this. But here was a fantastical vision of the power of electricity not just to power gadgets and toys, but life itself. Life could be sustained with enough understanding of electricity. Deaths could be prevented.

But it would be many years, and another death, before he was able to realize that vision in its greatest form.

After high school, Earl went into the Army, specializing in radar operations. When he was discharged, he took advantage of the GI Bill and attended the University of Minnesota, where he received his bachelor of science degree in electrical engineering. In short order, he began working on his Masters.

While working on that degree, he became acquainted with several people who worked at what was then Northwestern Hospital, now known as Abbott Northwestern Hospital, located in Minneapolis. His first wife, Connie, worked there as a Medical Laboratory Scientist; and when the hospital staff became aware of Earl’s ability to work with all things electrical, they asked if he could perform some much-needed repairs on some of their equipment.

These favors got pretty frequent, and it was Earl’s brother-in-law, Palmer Hermundslie, who suggested turning Earl’s electrical tinkering into a professional operation. And so, in 1949, Earl Bakken found Medtronic – he got the name by mashing up the words medicine and electronic. Their headquarters wasn’t a place where you would imagine advanced medical research happening; it was an old railroad boxcar they converted into a garage.

Earl didn’t really have very high expectations for Medtronic, he was happy to participate in his brother-in-law’s venture while he continued his education. At the time, he thought he might finish his doctorate and either teach or do research. In their first month of operation, their newly-founded hospital electrical repair business brought in a whopping $8. But then an event happened in Minneapolis that would not only change the trajectory of Medtronic, it would bring about his revolutionary innovation.

***

On the evening of October 31st, 1957, the twin cities in Minnesota - Minneapolis and St. Paul - experienced a blackout. One of the biggest metropolitan areas in America was suddenly without power. Since it was Halloween, I wonder if any of the city residents passed the time by telling ghost stories, the way Mary Shelley and her friends did. After all, they didn’t have electricity to light up their homes at night either.

But this had life-threatening consequences in the hospital. There was a ward for babies born with congenital heart or blood vessel defects. They’re often nicknamed ‘blue babies’, because the early lack of oxygen in their blood effects the color of their complexion. Dr. C. Walton Lillehei had been working on methods to sustain the lives of infants born with heart defects. And one of his innovations was a pacemaker; but not like the one we know of today. This one was external, a cumbersome system of tubes that needed to be plugged into an electrical outlet. For anyone who depends on such a device to stay alive, a blackout could be fatal. And this is precisely what happened to one of Dr. Lillehei’s young patients. On this Halloween night, the power failed, the twin cities were blacked out, the pacemaker connected to the wall outlet stopped working, and the boy’s heart connected to the pacemaker stopped working as well.

In the aftermath, Dr. Lillehei turned to Earl Bakken for help – there had to be something better than this. Earl agreed, and went to work.

Earl first attempted to keep a pacemaker operational by connecting it to a car battery. But, just like the old contraption that needed to be connected to the wall, it was too heavy and awkward to be a practical solution. But Earl knew about a newer piece of technology that was emerging - the transistor. For listeners who aren’t electrical engineers, a transistor is a device that can amplify an electrical signal or current. A small electrical current can go into the transistor, and emerge as a larger electrical current. If this sounds like magic, it certainly seemed so at the time – the scientists at Bell Labs who made it work had just shared the Nobel Prize in Physics. Nearly all modern electronics in the decades that followed used them.

With transistors, Earl was able to make pacemakers that were smaller and lighter, and generated less heat. In just four weeks he had a new prototype, still external, which could send electrical pulses to the patient’s heart by way of wires that went directly into the patient’s chest. As uncomfortable as that sounds, those wires could be easily removed without the need for any type of surgery. Dr. Lillehei almost immediately got it working on one of his patients – this would absolutely never happen in today’s medical world, where there’s a much more rigidly-defined process of testing and approval that can spread out over years.

Instead of a bulky device that sat on a cart and needed a wall outlet, Earl Bakken’s transistor model was only about the size of two packs of cigarettes, and it was battery powered – a patient with a pacemaker no longer needed to worry about blackouts. A patient wasn’t forced to lay in a hospital bed, tethered to a wall. This kind of freedom makes all the difference in quality of life and potential to heal. A patient could clip their pacemaker to their belt, or carry it in their handbag, and walk out in their community.

News of this radical advance made it all the way to Buffalo, New York, and an inventor named Wilson Greatbach. He believed that, with these new innovations, you could go beyond a wearable pacemaker, and actually install these devices inside the body. He teamed up with a renowned heart surgeon named Dr. William Chardack, and before long, they had succeeded. The pacemaker revolution had taken another step.

In 1961, Wilson Greatbatch sold the licensing rights to his innovation and his procedure to Medtronic. Suddenly, Earl Bakken’s electrical repair business based out of a boxcar was a multi-million-dollar enterprise. Earl and Wilson remained friends for many years, with Wilson taking on a consulting role with Medtronic.

In 1975, Earl founded the Bakken Museum in Minneapolis. It’s home to a world-class collection of historic and scientific and medical instruments, books, journals and manuscripts. The interactive experiences focus on the history and nature of electricity and magnetism, and an immersive exhibit dedicated to the inspiration behind it all – Frankenstein. The exhibit, aptly, is named “Mary and her Monster”.

Earl continued working with Medtronic until he retired in 1989, at which time he moved to Hawaii. And in case you are wondering - yes, Earl had his own invention implanted in him. Twice in fact. With the help of an internal pacemaker, Earl Bakken’s heart kept beating for a very long time. He passed away at his home in Hawaii on October 21st, 2018, at the age of 94.

PART FIVE

I can’t imagine what Mary Shelley would have thought, knowing that, by putting some advanced scientific ideas she had heard about into a scary story to amuse her friends, she created something which came back out of the realm of fiction to impact real science. That an invention inspired by her work would help preserve life, and extend people’s years of happiness and independence. I hope she would see it as a final victory – her life could have been solely defined by death and catastrophic tragedy. But her imagination changed the whole story, for herself and so many others.

And what’s next? Humanity isn’t done exploring the currents of life, and how to use them to fight disease and unlock new potential within ourselves. What is going to be the ‘pacemaker’ of the 21st century? One person with such an idea is Elon Musk. The famous, often controversial technological entrepreneur was one of the original generation of dotcom tycoons, helping to create PayPal. These days he is best known for his work with the Tesla motor company and their wildly-successful electric car, and SpaceX, which is developing a new generation of reusable spacecraft that could allow humanity to expand its footprint in the solar system. But those aren’t his only interest. He’s exploring what future technology can do to our brains.

In 2016, he founded a company called Neuralink, and recruited neuroscientists from multiple leading universities. Musk is funding much of their work personally, and they’re attempting to develop what they describe as an implantable brain machine interface. This device, in theory, would implant extremely thin wire strands into the brain, almost like a sewing machine into fabric. How thin? To put it into perspective, a piece of saran wrap is approximately 10 to 12 micrometers in width. A Neuralink thread would be between 4 and 6 micrometers in width, so less than half the width of a piece of plastic wrap.

With these implants, Neuralink is hoping to create a potential cure for a wide variety of ailments - dementia, spinal cord injuries, memory loss, hearing loss, insomnia, depression…the list goes on and on. The simple but revolutionary goal is to integrate human intelligence with artificial intelligence; using the external processing of a machine to repair or even replace lost function in the brain. Tests have even been performed on pigs, but human trials have repeatedly been pushed back. The intention is to start by focusing on cases of paralysis or paraplegia.

There are so many unknowns behind this concept, because once you have built this bridge, the possibilities are too great to comprehend. Imagine a stroke patient able to “speak” through a smart phone app just by thinking. Could you store your memories in the Cloud like a Google Doc, where they would always be preserved with perfect clarity? Could you download a college education? Or, in the dark side of that idea, could you be hacked, and threatened with paralysis if you didn’t pay a ransom?

Maybe this is where we need the imaginations of people like Mary Shelley. While science marches forward into regions that carry great risks, great rewards, and fundamental questions about our humanity, it needs a companion for when the path gets dark. Someone who remembers the impact these advances have on lives, on hearts and souls. Before there’s any kind of regulatory approval to put Neuralink into a test subject, authors and artists and futurists are going to be envisioning the possibilities. Hopefully, as Shelley did for Earl Bakken, they’ll find a way to warn us of the dangers, and show us how to use these seemingly-magical technologies to benefit us, while preserving what makes us human.

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Emily Wolfe and Evadne Hendrix; and our audio engineer is Dom Purdie. This story was prepared for us by Roseanne Sinclair, whose voice you also heard reading Mary Shelley’s words; check her out on her own excellent true crime podcast Killafornia Dreaming. Our senior story editor is Nicholas Thurkettle. Our lead researcher is Alex Bagosy; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.