Episode 24: Number Stations — Analog Spying in the Digital Age

Come walk this dark path with us and plunge into the history of spies. Learn from MF Thomas' first hand experiences about the uncrackable codes used to transmit information at ‘number stations.’

Listen To Learn More about:

Number Stations and how they allow spies to transfer information

Real life spies, Kendall and Gwen Myers

The North Korean Broadcast that stirred up alarm

“The Buzzer,” or the most ominous number stations

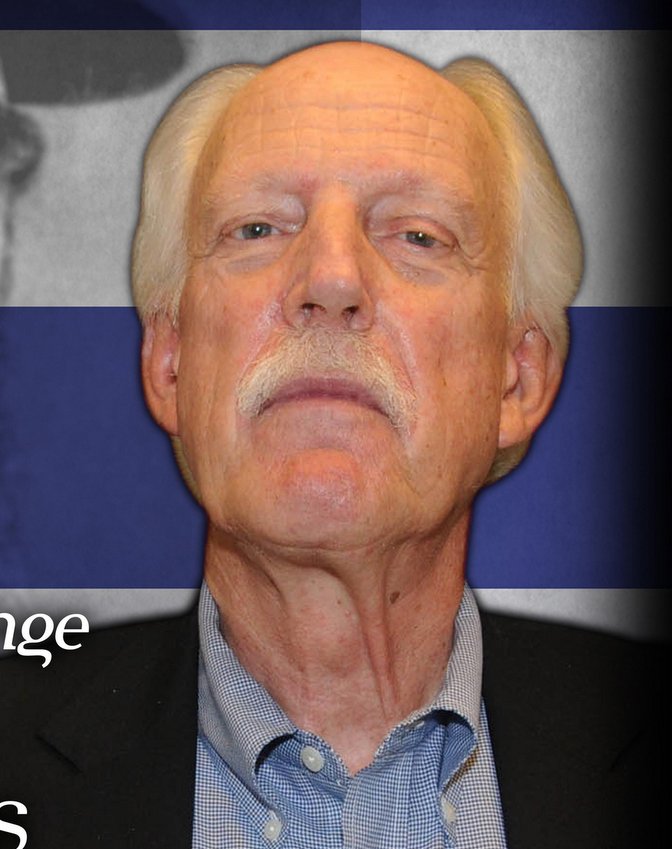

Kendall Myers

Novo Scotia -- Where Kendall Myers Grew Up Sailboating with his Mom

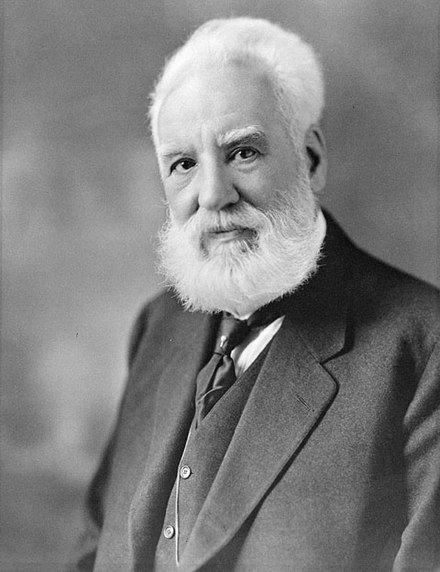

Alexander Graham Bell, Father of Kendall Myers

Hilton Hotel in Washington D.C.

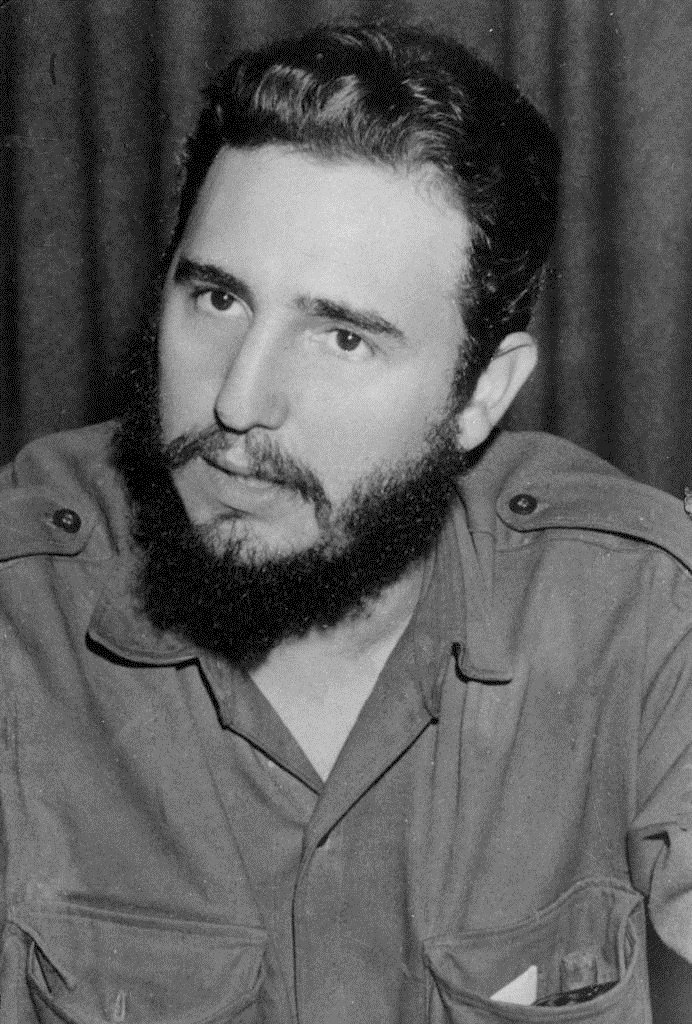

Fidel Castro 1950

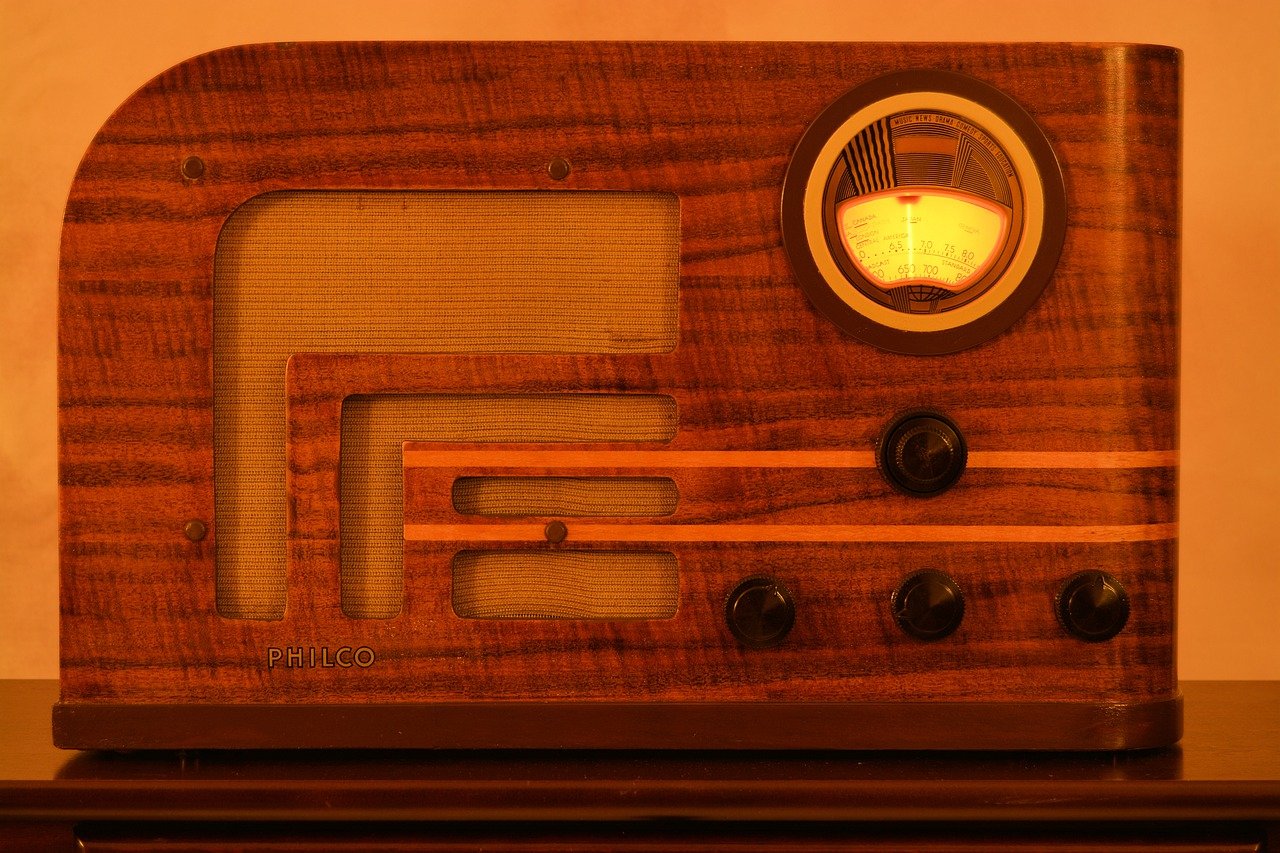

Vintage Shortwave Radio

Grimetown VLF Mast

References & Additional Reading

Vermont.gov: Worldwide Texting Statistics

USA Today: Internet Messages Sent 50 Years Ago

Washingtonian: Pying for Fidel the Inside Story of Kendall and Gwen Myers

Washington Post: DYN Content Article

Shortwave Radio Oddity Roundup

North Korean Secret Service Number Station

Daily Dot: Debug Russia Mystery

BBC: The Ghostly Radio Station that no one claims to run

Miaminew Times: Espionage is in the Air

IFL Science: Explorers Found their way Into the Abandoned Numbers Station

Gizmodo: Unexplained Signals of Russian Station

imgur: Number Stations Gallery

Reddit: I have visited an old Russian Numbers Station

Edward Jay Epstein Archived Spy Wars

Number Stations: How to Catch a Spy who Uses Number Stations

Full Script

The Capital Hilton is a historic hotel in Washington, D.C. It was built in 1943, originally called the Hotel Statler; and it sits on 16th St., just north of the White House. The luxurious lobby was actually featured in the Oscar-winning 1950 movie Born Yesterday.

I wasn’t booked to stay in the Hilton during a recent visit to D.C., but I made a point of visiting anyway. I wanted to picture some of the public areas for myself – like that lobby, or the bar where Kendall and Gwen Myers came to have a drink on the afternoon of June 4th, 2009. They wouldn’t look out of place here; they were part of Washington’s social elite. Kendall was a former diplomat who taught international relations and had a PhD from Johns Hopkins University. Gwen used to work on Capitol Hill as an aide to a Democratic Senator.

But on that spring afternoon in 2009, they weren’t there just for an idle beverage. They were meeting a man they knew only as Hector. In April of that year, Hector had introduced himself to Kendall Myers outside his classroom. Hector wished him a happy 72nd birthday, offered him a Cuban cigar, and claimed that he was offering greetings from an old friend. The old friend he named was a Cuban intelligence official; and Kendall took all this to mean that this Hector worked for the DGI, the Dirección General de Inteligencia, in the intelligence service for the Communist dictatorship of Cuba.

They met several more times, Kendall bringing his wife Gwen along. And then, at this meeting at the Hilton, their get-together moved from the bar up to a suite at the hotel, for greater privacy. During their conversation, Kendall and Gwen confirmed, out loud, their long history of passing classified intelligence from our government to Cuba’s. And that was all Hector needed to hear, because he wasn’t a Cuban spy at all – he worked for the FBI. Kendall and Gwen Myers were arrested, right here at the Capital Hilton.

For 30 years, they were known to Cuba’s spy network as agents 202 and E-634. But after their fateful meeting with Hector, they became federal prisoners 323487 and 323475, on trial for espionage.

Even as regular life happens in the big city of Washington, D.C., with regular people going to work, paying bills, raising families; there are other people, often in plain sight, following a dark path of secret meetings, spycraft, even treason. Kendall and Gwen Myers walked that path for decades, while keeping up the façade of a wealthy, well-connected couple, a blissful example of the American dream. The story of their betrayal reveals the sometimes-surprising reasons why people might turn on their own country. But even more interesting is that their most important piece of equipment wasn’t some James Bond-style super gadget – it was a simple, short-wave radio. Something anyone could buy. Even in a 21st-century world where digital technology connects the globe, there is still high-stakes espionage happening, all around us, every day, using analog techniques. And by the end of this episode, you’re going to learn how to tune in and hear it for yourself.

***

Hi, I’m MF Thomas and this is the My Dark Path podcast. In every episode, we explore the fringes of history, science and the paranormal. So, if you geek out over these subjects, you’re among friends here at My Dark Path. Since friends stay in touch, please reach out to me on Instagram, sign up for our newsletter at mydarkpath.com, or just send an email to explore@mydarkpath.com. I’d love to hear from you.

This week we will launch our new Youtube series! Starting with Episode 1 Von Zeppelin and the Airship, we are making videos to go along with the podcasts you listen to here. As always we will be grateful for your feedback. To show our gratitude, we will give away fifty free copies of my newest novel, Arcade. One to each of the first fifty commenters and subscribers on Youtube. So, keep an eye out for our video this Thursday at 2pm Eastern Standard Time.

Finally, thank you for listening and choosing to walk the Dark Paths of the world with me. Let’s get started with Episode 24: Number Stations – Analog Spying in the Digital Age.

PART ONE

I’ve been immersing myself in stories about spycraft and espionage lately, they’re at the heart of my next novel, Like Clockwork. It’s coming out next year and, unlike the speculative fiction in my other books, this is one is a straight-up, modern-day spy thriller. I’ve had great fun writing it. What was most remarkable to me in learning about this world is the human side of it all – technology is only ever as useful as the people operating it; and people still have the ability to thwart machine intelligence even while squarely in its sights. It makes sense, in a way – the world of intelligence is dependent on sources; and you don’t always have the opportunity to train your sources in advanced technology and techniques. You need to keep it simple.

The personal touch definitely made the difference in turning Walter Kendall Myers, Jr. into a spy for Communist Cuba. You would never have imagined it to look at him. He was a quintessential blue-blooded, prep school WASP. His great-grandfather was Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, and his home still had one of Bell’s sofas among all the silver and other antiques. His neighbors described him as a witty, curious intellectual; he didn’t read radical literature, he read the London Review of Books.

He lived his whole life in and around our nation’s capital, enjoying the kind of luxurious lifestyle and privilege that very few of us ever get to taste. Maybe the best example of this was his favorite pastime – sailing. His mother, Carol, taught him to sail onboard a 55-foot sailboat in Nova Scotia; and as an adult married to Gwen Myers, their greatest joy was the 37-foot yacht they used to travel the waters of the Chesapeake Bay. It was called the Helene, a $350,000 boat, swathed with mahogany and teak, built by master boatmakers in Kungsviken, Sweden.

It seems hypocritical to the point of absurdity – a carefree couple, flaunting their wealth, all while secretly betraying their country to a Communist dictatorship. Did they really think Communism was a better system? While we can never truly know peoples’ inner motives, the study of spycraft tells us that turning someone into an asset isn’t always about ideology. Sometimes it’s more like a long seduction – stroking the ego, creating the feeling that you are an important figure in a mighty struggle. And for some, living a secret, double life is a thrill all by itself.

The turning of Kendall Myers, as far as we know, started as far back as 1978. It was a depressed and bitter time in his life – three years before, he had been the driver in a car accident that killed a 16-year-old girl. He wasn’t found criminally responsible; but such a horror would stay with just about anyone. In 1977, his first marriage fell apart. And his writings indicate a persistent anger towards his home country – an obsessive feeling that it didn’t do enough to care for the poor and the sick, that it let oil companies dictate policy in the name of profit.

One of the great things about America is that anyone is free to criticize it; but this was not enough for Kendall Myers. While working at the United Nations in New York, he and two other employees of the State Department were invited to visit Cuba by a Cuban intelligence operative. He was on the island nation for two weeks. Was he wined and dined? Seduced? Persuaded that he alone could help save Cuba’s people from starvation and poverty, which Cuba would blame on America’s aggression and trade embargos?

Looking back at his career and published works, we see some hints. He had served in the Army in their Security Agency, where he received training in spycraft and was stationed in West Germany, listening to broadcasts from the former Czechoslovakia. Maybe he missed the excitement of espionage. He was also known in both academic and diplomatic circles for swimming against the current, offering provocative, iconoclastic theories about history and statesmanship – his doctoral dissertation even argued that British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was correct in attempting to appease Adolf Hitler prior to World War II.

The academic world depends on the existence of people willing to challenge and test assumptions, to play the Devil’s advocate. But the picture that begins to emerge – of a well-read, well-connected expert in statecraft who had actual espionage training and a seething grudge against his homeland – is one that would ping the radar of any intelligence service looking for a potential source.

From what information we have, it wasn’t about money for Kendall Myers. Cuba’s intelligence agents showed him a carefully-curated look at the so-called benefits of the Communist Revolution – their free hospitals, their museum full of exhibits describing previous revolutionary leaders that the United States had conspired against. This insidious argument – that the enemy of my enemy is my friend – seems to have been the one that turned Myers. Flattered to be told that his unpopular ideas and criticisms had been right all along, and blinded by his anger at America, he couldn’t see the poverty and oppression right in front of him. He became a fervent believer in the Cuban Revolution, and in Fidel Castro, whom he described as one of the greatest and most charismatic political leaders of his lifetime. After the Myerses were arrested and the FBI began questioning them about their decades of treason, Kendall and Gwen Myers said that they even spent four hours in Castro’s personal company during a trip there around New Year’s Eve, 1995.

When he sought his security clearance job at the State Department, it was precisely because it would allow Kendall access to sensitive information he could pass to his handlers. Ironically, he first applied for a job at the C.I.A., but was rejected. Gwen later reported that she was relieved by this. When you’re hired by the Central Intelligence Agency, you have to go through a series of polygraph exams; and her husband, she would say with no hint of irony, wasn’t a very good liar.

Kendall started at the State Department in 1985, and immediately commenced stealing secrets. From his position, he had access to documents and data from every American intelligence agency – FBI, CIA, NSA, and more. He was smart and careful in one respect – rather than stealing or copying sensitive documents, he would memorize them, recreating them outside of their secure facilities.

Gwen herself had no access to government secrets, she wasn’t working on Capitol Hill anymore. But Kendall enlisted her in his great mission to help the revolution, and she became an enthusiastic partner, helping to pass secrets off to Cuban agents. Her favorite method, she recalled, was switching shopping carts with them at the grocery store.

And then there was the short-wave radio that we mentioned. How did that play into their undercover work? It also came out at trial that they sometimes used encrypted e-mails, but it was shocking to me to think that such old-fashioned technology could play such a key role – after all, by the time the FBI arrested the Myerses in 2009, we were already on the 3rd generation of iPhones. What could a radio do that modern technology couldn’t?

Like I said, when you’re working with an undercover source, you want to keep things simple. And it turns out there’s a simple way for spies, military officers, criminals, anyone, to use a radio to send secret messages to one another that, if you’re careful, can’t be cracked by any listener or even any supercomputer.

They’re called numbers stations, and they’re broadcasting, right now, all around us. Let’s dive into this peculiar, captivating, unnerving world.

PART TWO

In one respect, short-wave radio isn’t secure at all. Literally anyone can listen in. Imagine trying to tune in your favorite radio station in your car and suddenly hearing secret instructions on where to retrieve a package.

But in some espionage situations, this is actually useful – if you’re trying to find the traitor in your midst by figuring out who a secret message is intended for, it’s a lot harder when it could be anybody. And because the person broadcasting the message and the person receiving it never have to meet, it makes it that much harder for observers to draw a connection between them.

A numbers station broadcast usually comes in two parts. First, there’s an identifier – a set of words, a piece of music, something recognizable. This is the signal that a code broadcast is coming. And then, you hear a long series of numbers; either spoken or in Morse Code. The message is hidden there.

Numbers stations have been used at least as far back as the first World War. Here’s an example of a real-world one in action.

That one is known as Swedish Rhapsody. It’s called that because of the melody that always plays on a music box right before a message is to be read. It operated for four decades on a disciplined schedule – always the same music, always the same voice that sounded like that of a little girl. It was actually coming from a primitive voice generating machine often used by the Stasi of East Germany – their ruthless state security service.

That recording was captured in 1982 – Swedish Rhapsody was well known, with a lot of people listening in – intelligence services, ham radio operators, even amateur codebreaking enthusiasts. But as far as we know, no one ever cracked the code. In 2014, declassified documents from Poland indicated that it was operated by the Polish Secret Police. Swedish Rhapsody stopped broadcasting suddenly just before the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, only for a copycat to suddenly begin elsewhere and continue reading numbers for at least another seven years. Was it the same group? We don’t actually know. Were any events in the Cold War affected by the information shared in these broadcasts?

The real trick to a numbers station is in making sure that, while anyone could hear the message, only your partner on the other side can understand it. The usual term for this is encryption. But can’t powerful computers break any encryption, figure out any code, any password? The science of hiding messages in code or trying to break that code is known as cryptography, and it has been around since the time of Caesar. Back then, you could simply send a coded message in a letter, or with light signals. But the development of radio created whole new opportunities.

In the First World War, the Germans managed to intercept the radio transmissions of the Russian Army, overhearing their orders to different divisions. This advantage led to devastating victories in East Prussia in 1914. Success in battle now meant that you had to assume someone was listening in.

But the game runs both ways. If you’ve learned how to decode the enemy’s broadcasts, you want to take advantage for as long as possible. As soon as the enemy knows that you’re listening, they’ll change their methods.

It was a lesson that our allies had learned the hard way. In the 1920’s, the Soviet Union operated a group in the UK called ARCOS – the All-Russian Co-Operative Society. It was a trade group, with the supposedly innocent purpose of supervising commercial transactions between the two nations.

But in 1927, the British were on a frantic search for a top-secret document which had gone missing from the War Office. And on May 12th, police suddenly raided ARCOS’s headquarters. There, they discovered a secret basement which could only be opened from the inside. Once they finally gained access, they found workers there, burning documents. ARCOS was a front for espionage activity – but here’s the problem: The British already knew this, and the raid didn’t produce anything useful. All it did was alert the Soviets to what the British knew.

The British may have remembered this catastrophic mistake during the saga of the Enigma Machine in World War II – as the British code-breaking team lead by the extraordinary Alan Turing broke the supposedly unbreakable Nazi encryption device. To use too much of the intelligence they acquired would have tipped off the Germans, whereas if they used only some, the British could appear to be merely very lucky in picking their targets.

Now, you don’t actually need radically-advanced technology to thwart a lot of code-breaking methods. All you need is what’s known as a “one-time pad”. This is a separate set of letters or numbers that act as the instructions for both coding and de-coding one single message. Even if an observer manages to acquire a copy of their pad, without knowing which message to apply it to, it’s just useless noise. In fact, in 1949 it was mathematically proven that, as long as the pad was at least as long as the message it applied to, and it was truly random, kept secret, and never used again, then it could not be cracked, even with infinite computational power.

One-time pads are ideal for numbers stations, and given how few of the most famous stations have been decoded, it’s a good bet that they’re in use.

But numbers stations aren’t just used for one-on-one communication between spies and informants. We recently spent two episodes discussing the dictatorship of North Korea and their involvement in a bizarre public assassination of Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un’s half-brother. Here’s a recording of a broadcast that suddenly emerged from North Korea just after midnight on July 15th, 2016. It’s now known as the V15 broadcast. Here’s the musical prelude, and a little bit of the coded message that followed:

Here’s a translation of some of that message. Quote: “From now on, I will give review work for the subject of mathematics under the curriculum of a remote education university for exploration agents of the 27th bureau. On page 459, question number 35; on page 913; question number 55; on page 135, question number 86…” End Quote. And here’s an extra-intriguing detail – while the broadcast originated in North Korea, the speaker is using a South Korean dialect. Why would they do that? Who were they talking to?

The South Korean government reacted to this broadcast with immediate alarm. Given North Korea’s massive army and history of open hostility, it was reasonable to wonder if this signal might be the sudden prelude to a coordinated terrorist attack, or even an out-and-out invasion.

There were more of these V15 broadcasts, in fact there was one every week for almost three years. After that, things became less regular; and as of right now, the last broadcast we know of happened on March 12th, 2020.

There’s a psychological element to the use of a numbers station – it’s frightening to know that the enemy is doing something, but you can’t tell what. Maybe the most ominous numbers station in history is known as “UVB-76”; but it has a nickname that’s easier to remember: The Buzzer.

The Buzzer was first discovered in 1982, but it’s still active today. You can listen to it right now. What you’ll hear is a background of monotonous static, interrupted every few seconds by a tone that sounds a little like a foghorn.

But if you listen long enough; once in awhile, a Russian voice will come on. Here’s a sample of that, captured in August of 2010:

Listeners have been scrutinizing The Buzzer for almost 40 years. They’ve noted a lot of changes in that time. The first version of the signal was just a two-second beep, repeating endlessly. Sometime after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 90’s, it changed to the buzzing noise we still hear today. By that time there was already an impassioned community of listeners recording observations and exchanging theories.

What they figured out was that the Buzzer isn’t a recording, it’s a live signal, created by an active microphone being placed near a speaker. And if you listened keenly enough, you could actually overhear faint conversations happening in the room where the microphone is placed. There’s something about this detail which is irresistible to the imagination – there’s a real room, with real people in it, right now, somewhere on Earth, creating this signal, and after decades of paying attention we still don’t know what they’re doing.

There’s no discernible pattern to the appearance of the Russian voice. The buzzing will stop just long enough to read a short, encoded message. Early on, these announcements seemed exceedingly rare, but it’s possible there simply weren’t enough people monitoring to notice them. Now there are Buzzer enthusiasts observing around the clock. Nine years ago, a pair of explorers visited the closed Russian military base where they believe the first version of the Buzzer was transmitted from. They shared some pictures and observations, some of the details were ominous – like dark, underground tunnels with toxic smells. Others are strangely mundane, like a small piece of crude graffiti, someone at the base seemingly insulting a co-worker behind her back.

Recently, a photograph was circulated from a Russian military enlistment station, where a card identified the 4625kHz frequency that the Buzzer broadcasts on. Maybe this means that this is simply their equivalent of our Emergency Broadcast System – a fast, low-tech fallback for communicating with your Army in a crisis. But if this were so, given the millions who have served in the Russian military, and the Soviet military before that, in all these years, wouldn’t one defector have confirmed an explanation this simple?

There’s another theory about signal UVB-76, a much darker one. In this scenario, what’s important about the Buzzer isn’t what it’s doing, but whether or not it’s operational at all.

In war gaming they call this a Dead Hand signal. It’s the ultimate failsafe in a world of nuclear weapons. If a country’s leadership is suddenly wiped out in a surprise attack, a Dead Hand mechanism can trigger an automatic full-scale counterattack. As part of the brinksmanship that was constant during the Cold War, a Dead Hand would serve as a deterrent – even if you wipe out our whole senior command structure in one blow, all our missiles will be launched anyway. I don’t know if it’s still taught in schools, but throughout the arms race between the United States and Soviet Union, many tactics were designed around this concept, which was known as Mutually Assured Destruction. M, A, D. Mad.

In 1983, Stanislov Petrov, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Soviet Air Defense Forces who was on duty at a nuclear early-warning station, received a false alarm that the United States had just launched five nuclear missiles. He wasn’t supposed to think about this, he wasn’t supposed to examine the data or wait for confirmation. He was supposed to fire the Soviet nuclear arsenal immediately. All these procedures were designed for maximum aggression, to take any doubt and circumspection, any humanity, out of the equation. But Petrov disobeyed his orders, delayed the launch, and then learned that they’d received a false signal. The humanity of this one soldier in a system that seemed designed to all but guarantee mass annihilation, stopped the Cold War from ever turning hot. Let us know if you’d like to hear more about Stanislav Petrov, he’s absolutely worthy of a spotlight on our show.

And as for the Buzzer? Is it another part of this network of failsafes, these systems of Mutually Assured Destruction? Whatever it is, it’s still alive, still active, its purpose still ominously beyond our understanding.

PART THREE

The Soviets certainly weren’t alone in the use of numbers stations for espionage. The United States ran a famous high-level informant using one. His name was Anatoly Filatov, and in him we find another example of how intelligence sources are cultivated, exploited, and hunted by those they have betrayed.

The highest echelons of the Soviet Union’s military and intelligence powers were notoriously difficult to penetrate. The C.I.A. even admitted to Congress that after the arrest of a high-ranking Soviet officer who was feeding them information, they didn’t have a single, functioning mole with access to top-level secrets for 14 years. For all the bugging, eavesdropping, and theft you can commit, there’s nothing as valuable in espionage as what they call HUMINT – Human Intelligence. And part of the problem for the C.I.A. was that the K.G.B. had their own moles, sabotaging America’s efforts to identify and recruit moles of its own. That is, until Anatoly Filatov.

Filatov was born in 1940, and while we don’t know much about his childhood or education prior to adulthood, we know he served in Laos from 1965 to 1968 as a military translator; and that upon his return he attended the Military Institute of Foreign Languages, where he studied French. Most of his work appears to have been carried out under the umbrella of the GRU, the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Soviet Military Agency. He wasn’t trained to be a spy, he was a scientist and linguist. But the C.I.A. made a spy out of him, seemingly against his will.

Remember when we discussed the case of the Myerses earlier, and how Cuba’s intelligence service seemed to apply the tactic of appealing to Walter Myers’s ego, his frustration with American society, and his desire to feel like an important figure in a global struggle to make the world a better place? The case of Anatoly Filatov. is different altogether. In 1974, when he was assigned to work in the Soviet Foreign Ministry in Algiers, he had an affair with a woman named Nadia. And the C.I.A. took many pictures of this affair, to use as blackmail. Because Anatoly had a wife and children back home. We don’t know where this woman Nadia came from, or if they knew they were working on behalf of the CIA when they had their liaison with Anatoly Filatov; but seduction for the purposes of coercion and blackmail is one of the oldest techniques in spying. It’s known as a honeypot.

Filatov’s code name in the CIA was “Trianon”. He was given detailed procedures and instructions to follow for when he was transferred back to Moscow. He was provided a spy camera for photographing documents, a park bench was designated to be what’s known as a “dead drop”; a place where he could leave the microfilm from his spy camera, to be retrieved later. He was encouraged to befriend and charm as many co-workers as he could, in order to increase his access to sensitive material. And a dedicated numbers station was set up to broadcast instructions to him. It emanated from Frankfurt, Germany, and sent out coded messages twice a week. Knowing that their station would be overheard by the Soviet KGB, the CIA started regular broadcasts before Filatov even returned to Moscow, to make it that much more difficult to identify the intended target of their messages.

At this point in the Cold War, the KGB kept tabs on every U.S. citizen in Moscow. So all of these espionage methods – the dead drops, the numbers stations, were designed so that there would never be any visible points of contact between Filatov and his handlers. The pressure was on almost immediately – less than a year after he started smuggling out information, the KGB had reached the conclusion that there was an active American mole with high-level access. They surmised correctly that the numbers station in Frankfurt was connected. They listened obsessively, and while they were never able to crack the code of the broadcasts, it still played a key role in discovering Filatov.

They stepped up their monitoring of CIA activity, as well as anything going on at the U.S. Embassy. If known American agents got more active, it could be a sign that there were stolen documents out there to retrieve.

On February 9, 1977, the KGB intercepted a package bound for the US from Moscow. It contained a letter, a seemingly innocent one, written by a tourist contacting loved ones back home. But, when the letter was chemically-treated, an entirely different message was revealed; one concealed by a complex code. Whoever this supposedly innocent tourist was, they had espionage training, and knew Russian.

Remember that sometimes it’s more valuable in intelligence work to hide that you’ve learned something about your adversary. So the KGB let the package continue on to its destination. But suddenly they had a way of narrowing their search. They started looking for letters sent to destinations outside of the Soviet Union on the days following a broadcast from the Frankfurt station. This is the part of spying you don’t often see in movies and TV shows; the meticulous, often exhausting work of sifting through massive volumes of information, with only a few clues to guide you. But incredibly, this was enough – the KGB was able to identify a post office where several of these coded messages had been sent from.

Meanwhile, they were obsessively analyzing the handwriting of the letter, looking for matches among the signatures of government officials and officers. Their initial search found more than 2,000 potential candidates; one of them was Anatoly Filatov, who was now working in the Ministry of Defense. He had no idea yet, but the net was tightening around him.

A profile analysis was made of his personality – it described him as, quote, “weak, dependent, and needy.” In a system built around mistrust and paranoia, you can find reasons to suspect anybody – the Myerses in America were anything but weak and needy, but they turned traitor nonetheless. But as the list of suspects narrowed and more attention was paid, Filatov was attracting more and more scrutiny.

They decided to bug his home. This actually proved difficult; he lived in an apartment complex designed to be difficult for outsiders to enter. But when his wife and children left to visit their parents, the KGB was able copy the main door key – they infiltrated his home and rigged it with surveillance equipment. With that, they soon had all the evidence they needed. Even though the numbers station had worked flawlessly, they still found their mole with brute force persistence and a few lucky guesses.

Anatoly Filatov was arrested on August 7th, 1977. Under interrogation, he told the story of Nadia, the way he was recruited by coercion, how he was paid $40,000 plus 20 gold coins for his treason. And once again, the CIA was left without a high-level source in Moscow. The KGB had won this round.

In 1981, the New York Post reported that Filatov had been sentenced to death by firing squad. But for reasons we still don’t know, this never happened. His sentence was commuted to 15 years in a labor camp – and he only served part of it, as he was able to speak with French journalists about his experiences in 1989. His location now, even whether he is alive or dead, is unknown.

Much of what we know about his case actually comes from a KGB training manual that surfaced after the fall of the Soviet Union. His successful capture is presented as a real-world test case in how to discover moles who use numbers stations.

PART FOUR

Let’s come back to where we started; to Kendall and Gwen Myers at the Capitol Hilton. Just like in the Filatov case, they weren’t captured because of the numbers station – yet another endorsement of this remarkable technique for hiding communications right in the open.

By the spring of 2009, the FBI had arrested a number of Cuban spies, and after interrogating them and analyzing their activities, had high confidence that there was a Cuban intelligence source with access to top-level secrets of our government. By this point, the Myerses were semi-retired, enjoying their wealth, their social circles, and that beautiful boat. They hadn’t even stolen any government secrets for awhile. How the FBI identified them hasn’t been revealed in much detail, but once the agent who called himself Hector made contact, getting them to convict themselves was all too easy.

After he introduced himself and gave Kendall that Cuban cigar, they met at a nearby bar the next day. Kendall brought Gwen with him. Hector didn’t ask them to steal any secrets, it was a general conversation; asking them if they had any insight into how the new administration of President Obama viewed the Cuban government. This is interesting to me, because it reinforces that, for Kendall at least, the leverage point that worked, time and time again, was appealing to his considerable ego.

Without any prompting, they confessed to their past activities for the Cuban government. In Kendall’s words, quote: “We have been very cautious, careful with our moves and, trying to be alert to any surveillance if there was any.” End quote.

It was Gwen who shared that they still possessed the short-wave radio that the Cubans had provided. They hadn’t listened to it in a long time, though. They liked Hector, and agreed to meet with him again.

In a series of private meetings at hotels throughout April and May, they spilled even more details about their exploits in service of Fidel Castro fuh-dehl caas-troh]: Kendall’s methods for stealing confidential documents, how Gwen helped him deliver these secrets to the Cubans. Maybe they were excited that they finally had someone they could brag to, about how clever and successful they had been for so long. But all that subterfuge came undone because of their fatal mistake of trusting Hector. By the time they met him at the Capitol Hilton on June 4th, there were hidden cameras in the room with him, documenting all their confessions in irrefutable detail. The judge in their case later said, “I see no sense of remorse. You are proud of what you did.”

In these two high-profile cases, where both our government and the Soviet government flushed out moles who used numbers stations, the stations themselves performed their function perfectly. There’s something invigorating about coming back up this dark path, back into the modern age, with the knowledge that the spy game is still very much a human one. That the most radical technology invented isn’t necessarily any more secure than a string of numbers read out over the open air.

It seems that the element that makes so many intelligence operations succeed or fail is the people involved – how careful they are, how valuable their access is, and what it was in their personality that compelled them to play the spy game to begin with. Whether it’s greed, or pride, or lust and shame, it’s far easier to find a weakness in a person. If you’ve got a secret – what would it take to get it out of you?

***

Thank you for listening to My Dark Path. I’m MF Thomas, creator and host, and I produce the show with Ashley Whitesides and Evadne Hendrix; and our creative director is Dom Purdie. I took the lead on preparing this story, since it arose out of research for my upcoming spy thriller novel Like Clockwork. But, like always, I had the indispensable support of our senior story editor, Nicholas Thurkettle, and our fact-checker Nicholas Abraham; big thank yous to them and the entire My Dark Path team.

Please take a moment and give My Dark Path a 5-star rating wherever you’re listening. It really helps the show, and we love to hear from you.

Don’t forget to check out the start of our youtube series this Thursday at 2pm Eastern.

Again, thanks for walking the dark paths of history, science and the paranormal with me. Until next time, good night.